KI News

Anders Ekbom acting Pro-Vice-Chancellor from 1 January

Professor and physician Anders Ekbom has been appointed acting Pro-Vice-Chancellor of Karolinska Institutet from 1 January 2017. He succeeds Henrik Grönberg, who has been acting Pro-Vice-Chancellor since 7 March 2016.

Anders Ekbom is Senior Professor in Epidemiology at the Department of Medicine in Solna and in 2016 received Karolinska Institutet’s Grand Silver Medal, which the university awards for significant contributions to Karolinska Institutet. Professor Ekbom has among other things “played a major part in developing cooperation between KI and Karolinska University Hospital” and will play an important role in KI’s collaboration with Stockholm County Council during his term as Pro-Vice-Chancellor.

EUR 15 million to KI-coordinated project on MS treatment

A new international partnership called ‘MultipleMS’, coordinated at Karolinska Institutet, has been awarded 15 million euro from the European Commission to find novel and better treatments for Multiple Sclerosis (MS).

In this project, universities and companies across 12 European countries and the US will unite efforts to tailor the development and application of therapies to the individual MS patient.

“What is truly unique about this project is the scale of the partnership and the huge amount and different kinds of patient data that will be combined, such as clinical, genetic, epigenetic, molecular, MRI and lifestyle data”, states Ingrid Kockum, Professor at Karolinska Institutet and coordinator of the project.

MS is an immune-mediated disease affecting the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). Over two million persons worldwide have been diagnosed with the disease and a cure is not yet available.

The result of current treatments varies strongly from patient to patient, which makes it unpredictable which patient will benefit from what treatment.

“Our novel approach is to take the multifaceted nature of MS as the starting point for identifying personalized treatment opportunities in the disease”, says Ingrid Kockum.

More than 50,000 MS patients and 30,000 healthy individuals are included in the project, which builds on the foundations and research networks laid out by earlier consortia such as the Nordic MS genetics network, the International MS Genetics Consortium (IMSGC) and International Human Epigenome Consortium (IHEC).

Martin Ingvar given new role in Karolinska Institutet’s management

Martin Ingvar has been appointed KI’s Deputy Vice-Chancellor with responsibility for coordinating issues concerning external collaboration. The position is a new one in the management organisation and the aim is to support the university’s efforts to attract donations.

Work on donations is coordinated within the Development Office at Karolinska Institutet, to which the assignment belongs. Many people work to bring in donations, also known as fundraising with the help of philanthropic support, at Karolinska Institutet. But now a coordinating, strategic function is to be instituted in the university’s management to support the vice-chancellor.

“This is in line with Karolinska Institutet’s Strategy 2018, where philanthropic support is one of the areas that are given particular emphasis. Clarity and continuity are needed in our dealings with our donors and there we need a deputy vice-chancellor who can put in the necessary time and energy and provide support for the vice-chancellor,” says acting Vice-Chancellor Karin Dahlman-Wright.

“Fundraising and philanthropic support are important for a university today”, she explains. Putting the issues on the management’s table is fully in line with how universities in other countries work and Martin Ingvar has worked with such matters before.

His earlier appointment as KI’s Deputy Vice-Chancellor with special focus on the healthcare of the future ended at the turn of the year – perfect timing to be able to take on his new assignment. He will keep some of his earlier responsibilities but will now focus on making Karolinska Institutet stand out in fundraising contexts.

“We need to forge external relations in a number of areas, for example long-term pioneering projects for which regular funding is not available. In order to be considered, Karolinska Institutet needs a well-reasoned policy to achieve it, a more systematic process and a strategy established within the organisation,” says Martin Ingvar.

Interfacing with donors and distributing funds internally will still involve many people.

“I will be responsible for reading the map,” he says.

Text: Madeleine Svärd Huss

Good long-term results of obesity surgery in young people

Bariatric surgery on teenagers gives results that are equally as good as for adults, but the operations carries complications. Five years after surgery, the patients weighed on average 28 per cent less than beforehand, a new study shows.

“Teenagers and adults who have undergone bariatric surgery exhibit remarkable similarities,” says Torsten Olbers, docent at the Sahlgrenska Academy and consultant at Sahlgrenska University Hospital. “Seriously obese young people who do not have surgery continue instead to increase in weight.”

The study he led compared 81 teenagers who had a so-called gastric bypass with an equal number of teenagers in receipt of conventional treatment and a group of adults who had also had a gastric bypass. 65 per cent were women and 35 per cent men.

The teenagers who were operated on were between 13 and 18 at the time of surgery, with an average age of 16 and an average BMI of around 45. In many cases, their obesity had already caused complications, such as altered blood lipid levels, high blood pressure, fatty liver, type 2 diabetes or a precursor of diabetes.

Considerable weight reduction

“It is the most seriously obese young people we’re talking about, and without surgery virtually all of them remain large for the rest of their lives,” says Dr Olbers. “It is especially evident in the young people that there is a strong underlying genetic predisposition for serious obesity. This is no lifestyle choice they have made.”

The teenagers who did not receive surgery continued to gain weight during the five-year period by an average of 10 per cent, and 25 per cent of them were operated on during the follow-up time since becoming adults. This compares with a 28 per cent weight loss in those who underwent gastric bypass surgery.

However, 25 per cent of the teenagers who had received surgery also suffered complications that required another operation within five years, roughly half of them for ileus and half for gall stones.

“It came as a surprise to us that young people also had gall stones, something that we have seen in adults with severe weight loss,” says Dr Olbers. “The young people also had the same frequency of ileus as the adults, a complication that we can now prevent by closing the so-called ‘slits’ during surgery.”

Follow-up and support

The operation, which is performed using keyhole surgery, takes roughly an hour and involves attaching the small intestine to a small gastric pocket just under the oesophagus. The stomach is left in place, and produces gastric juices that enter the system, along with the bile etc., further down. This means that in effect ingested food passes direct into the intestines.

“It’s not that the system comes to a stop,” explains Dr Olbers. “The operation changes the basic signals of hunger and satiety. You don’t get so hungry and feel full more quickly, even in your mind.”

There is, however, a risk of vitamin and mineral deficiency after a gastric bypass owing to the reduction in food intake and the re-connection of the intestines. This was obvious in the young people, who tended not to take the recommended supplements.

“It’s essential that we continue to monitor these young people, especially as they have many decades of life left ahead of them,” adds Dr Olbers.

The study followed up patients at several locations around the country and also involved researchers at Lund University and Karolinska Institutet, where Claude Marcus is professor of paediatrics.

“It’s time to start integrating bariatric surgery with the treatment of seriously obese young people,” he says. “But they must be monitored over the long term since our results also show that some young people need a lot of support to handle the post-operative situation. Bariatric surgery is no quick fix.”

Publication

Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in adolescents with severe obesity (AMOS): a prospective, 5-year, Swedish nationwide study

Dr Torsten Olbers, PhD; Andrew J Beamish, MD; Eva Gronowitz, PhD; Carl-Erik Flodmark, PhD; Jovanna Dahlgren, PhD; Gustaf Bruze, PhD; Kerstin Ekbom, PhD; Peter Friberg, PhD; Gunnar Göthberg, PhD; Kajsa Järvholm, PhD; Jan Karlsson, PhD; Staffan Mårild, PhD; Martin Neovius, PhD; Markku Peltonen, PhD; Claude Marcus, PhD.

Published online 5 January 2017, The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30424-7

Protein that inhibits and reduces the effects of chemotherapy identified

Researchers at Karolinska University Hospital and Karolinska Institutet and their colleagues from Science for Life Laboratories (SciLifeLab) and Heidelberg University have identified a protein that determines the efficacy of cytarabin – the most important drug for treating acute myeloid leukaemia. Their results are published in the scientific journal Nature Medicine.

Some 350,000 people around the world are diagnosed every day with the aggressive form of blood cancer known as acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), only 25 per cent of whom survive beyond the fifth year. Over twenty years ago, survival rates were improved by the use of high doses of the cytotoxin cytarabin, but the efficacy of the drug declines over time in some patients. The mechanism of this resistance has remained something of a mystery; however, in the present study, which involved analyses of 300 patients, the researchers show that a protein called SAMHD1 plays a major part in this by reducing the effect of cytarabin in leukaemia cells, and that leukaemia cells with lower levels of SAMHD1 respond better to the drug. The team was also able to make leukaemia cells more sensitive to cytarabin by blocking the protein.

“Our results go a long way to unlocking the pharmacology of cytarabin in the treatment of leukaemia,” says Nikolas Herold, researcher at Karolinska University Hospital and Karolinska Institutet. “We hope that the results will eventually help to improve the treatment of AML using cytarabin combined with substances that block SAMHD1. More studies will be needed first, however.”

Translational collaboration

Dr Herold is co-lead author of the paper with Dr Sean Rudd. The study was conducted in collaboration with colleagues from Jan-Inge Henter’s and Thomas Helleday’s research groups at Karolinska Institutet and Torsten Schaller’s research group at Heidelberg University, amongst others.

“The results are the product of a successful translational partnership between researchers from Karolinska Institutet, Karolinska University Hospital and SciLifeLlab,” says Dr Herold.

Funding

The study was financed by grants from a number of bodies, including the Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, the Cancer Research Funds of Radiumhemmet, the Knut & Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Swedish Pain Relief Foundation, the Torsten and Ragnar Söderberg Foundation, the David and Astrid Hagelén Foundation, Stockholm County Council (ALF), the German Research Foundation (DFG) and, in part, the German department of research and education via the Immunoquant project and the HIVERA: EURECA project. S.G.R. is in receipt of an EMBO Long-Term Fellowship. Chemical Biology Consortium Sweden is financed by the Swedish Research Council, Science for Life Laboratories and Karolinska Institutet.

Publication

Targeting SAMHD1 with the Vpx protein to improve cytarabine therapy for hematological malignancies

Nikolas Herold, Sean G Rudd, Linda Ljungblad, Kumar Sanjiv, Ida Hed Myrberg, Cynthia B J Paulin, Yaser Heshmati, Anna Hagenkort, Juliane Kutzner, Brent D G Page, José M Calderón-Montaño, Olga Loseva, Ann-Sofie Jemth, Lorenzo Bulli, Hanna Axelsson, Bianca Tesi, Nicholas C K Valerie, Andreas Höglund, Julia Bladh, Elisée Wiita, Mikael Sundin, Michael Uhlin, Georgios Rassidakis, Mats Heyman, Katja Pokrovskaja Tamm, Ulrika Warpman-Berglund, Julian Walfridsson, Sören Lehmann, Dan Grandér, Thomas Lundbäck, Per Kogner, Jan-Inge Henter, Thomas Helleday & Torsten Schaller

Nature Medicine, published 9 January 2017, doi: 10.1038/nm.4265

Disaster Medicine at KI collaborating with the WHO

The Centre for Research on Health Care in Disasters at Karolinska Institutet has been designated a WHO Collaborating Centre by the World Health Organization. “Collaboration with the WHO will now be even closer,” says Centre Director Johan von Schreeb.

Its status as a Collaborating Centre will allow KI to share its knowledge. “The fact that our collaboration with the WHO is now on a more formal footing is also proof that our activities are important to the WHO,” says Johan von Schreeb, researcher and specialist in disaster medicine.

“We do research on concrete problems where the university can help devise solutions. How do you for example put research into practice and ensure that it is as evidence-based as possible?

It’s a challenge to work systematically and based on evidence in a disaster zone but it must be everyone’s endeavour to do so,” Johan von Schreeb goes on. On his next visit to Mosul he will be accompanied by graduate student Andreas Älgå, who conducts randomised studies of different ways of treating war injuries.

The centre will provide the WHO with expert advice relating to disasters and conflicts and work with policy drafting and research in conjunction with evidence of the measures taken.

“We’ll be helping the WHO in environments with sparse resources where they need our expertise,” explains Johan von Schreeb.

The Centre for Research on Health Care in Disasters has already collaborated with the WHO on a number of occasions: in connection with the Ebola epidemic in West Africa and the Nepal earthquake and during the current fighting in Mosul in Iraq. The centre also contributed expert knowledge when the WHO drew up its guidelines for international field hospitals in disaster areas. The document “Classification and minimum standards for foreign medical teams in sudden onset disasters” states that responses must be based on expertise rather than good intentions.

“You can’t just go down to a disaster zone with out-of-date material from your local surgery department. Having a kind heart isn’t enough: you need a cool head with knowledge and experience. Aid work must have quality and the resources must be used efficiently and effectively,” says Johan von Schreeb.

The World Health Organization collaborates with over 700 organizations in more than 80 countries, which have been designated Collaborating Centres. In all, there are seven such collaborations currently ongoing in Sweden.

Text: Ann Patmalnieks

In the words of KI’s new chairman, “We need to start afresh.”

Mikael Odenberg took over as Chairman of the Board of Karolinska Institutet on 1 December 2016 and has two urgent matters to attend to: recruit a new vice-chancellor and clean up after the Macchiarini case. The minister responsible, Helene Hellmark Knutsson, says that the partly new board is expected to restore confidence in Karolinska Institutet and Swedish medical research.

“Oh my,” I thought. “Then I decided to say yes,” says Mikael Odenberg.

Why the choice fell upon him is a question for others to answer. He has no academic qualifications to speak of, not having completed his studies at university and the Stockholm School of Economics. He says his guess is that it has more to do with his broad experience of controlling authorities, an area where, according to the investigations conducted during the autumn, Karolinska Institutet has fallen far short of the mark.

Mikael Odenberg describes his background as a whole lifetime in the public sector, most recently as Director-General of Svenska kraftnät, Member of Parliament for fifteen years, and Minister for Defence in Fredrik Reinfeldt’s government, a post he resigned from in protest against cuts in the defence budget. And his experience in the health care sector, among other things as a member of Stockholm County Council between1976 and 1991.

“That might be of use to me at a medical university. And I’ve also led change processes.”

Reviewing the investigations

Now he’s getting to lead another. Karolinska Institutet is to rise again after ”a first-class scandal”, as Mikael Odenberg puts it.

“It’s naturally not the Board or its chairman who decides how people view Karolinska Institutet. In my honest opinion, it’s going to be a fairly long journey. Many people are saying ‘we’ve read so much about Macchiarini and we’re getting rather tired of it – let’s stand up straight and move on’. But in that respect I think they are tending to trivialise what has happened,” Mikael Odenberg goes on.

“The Board has the ultimate responsibility but many people have to do their part,” he adds.

At an extraordinary board meeting at the end of January, the Board, with its new government-appointed members, will meet for the second time.

“We need to start afresh,” says Mikael Odenberg.

At the meeting, investigators Sten Heckscher and Kjell Asplund and internal auditor Peter Ambroson will present their findings in the Macchiarini case.

“And there the Board needs to form a picture of to what extent we agree with the conclusions or whether we are of a different opinion. And if we agree – what measures have been taken and if they are sufficient.”

Looking at the vice-chancellor’s recruitment

The recruitment of a new vice-chancellor, which was suspended following the autumn’s replacement of external board members, needs to start afresh.

The new Board must own the process. This means that decisions concerning the recruitment committee, requirement profile and schedule will be taken again. This will be done at the extraordinary meeting in January. Some adjustments will be made but there is no reason to expect any major changes,” Mikael Odenberg says.

At the same time, he emphasises that Karolinska Institutet needs a vice-chancellor with very good leadership qualities, the ability to make all necessary decisions, and great integrity. He wants to lay greater emphasis on leadership qualities than on scientific excellence – “There’s not a lot of research to be done in the vice-chancellor’s office.”

“But the person appointed Vice-Chancellor of Karolinska Institutet must of course have broad support and respect among 375 professors, so you can’t propose a person with mediocre qualifications,” Mikael Odenberg says.

A long-term issue: the organisation

Mikael Odenberg’s appointment as Chairman of the Board lasts until 2020. Over this period he will also have to deal with long-term issues that he has not yet had time to look at properly: the organisation, finances and “the eternal question” of making clear the distribution of responsibilities between Karolinska Institutet and Karolinska University Hospital.

“Many say that Karolinska Institutet’s organisation is rather dysfunctional as it stands today. It’s been in place for more than 20 years so it’s something we need to look at, along with how control is intended t be exercised. How does leadership work at KI? We are not only an institution of higher education and a research institute, we are also an authority and have a number of requirements to live up to. And it’s been a little so-so in that respect,” says Mikael Odenberg.

“But the fact of course is that the vice-chancellor who is appointed must take a very active part in this, so we mustn’t come up with too many things before we actually have a new vice-chancellor.”

Text: Madeleine Svärd Huss

Photo: Gustav Mårtensson

Mikael Odenberg on:

… his opinion of Karolinska Institutet: “I have considered Karolinska Institutet to be our number one university and I still do. KI holds a very prominent position, not only in Sweden but around the world. And has delivered world-class research over the years. It’s also beyond doubt that the Nobel Assembly, although it’s not actually part of the university, has also helped put KI on the map.”

… the effects of the Macchiarini case: “Confidence in Swedish science and research is generally speaking fairly high, but it’s quite clear that confidence in KI has taken a fall. It would be stupid to say anything else. And it’s also clear that this is having serious effects within KI. I can imagine it’s been difficult to ignore: people have more or less been forced to take a position one way or the other. Nor has the Nobel Assembly escaped unscathed, for example.

… his public beef with the Expressen newspaper carried on in social media: I have not criticised Expressen or anyone else for their examining of me or anything else. What I have criticised is this distorted sensational journalism where papers withhold important facts and try to put a picture to something that will convey an impression of scandal. I have spent my whole life in the public sector and investigative journalism is incredibly important. I am open to scrutiny, naturally, but the media also need to be able to take criticism.”

New software makes CRISPR-methodology easier

Scientists at Karolinska Institutet and the University of Gothenburg have generated a web-based software, Green Listed, which can facilitate the use of the CRISPR methodology. The software is published in the journal Bioinformatics and is freely available through greenlisted.cmm.ki.se where also information texts and films are available.

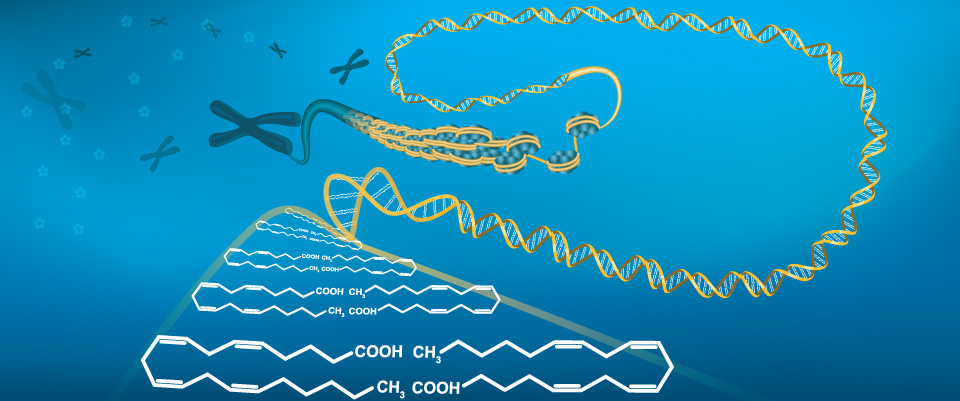

Cells are very small and builds up an organism. A human has about 100 times as many cells in its body as there are people on earth. Inside a vast majority of these cells are long chains of DNA. These DNA chains affects how different cells look and behave. CRISPR is a research method that can be used to rapidly study how different portions of the DNA directly affect cells. Using this method, researchers can gain insights to the cause of diseases and give suggestions for how they can be treated.

"We use the CRISPR methodology to study both immune cells and cancer cells. The goal is to develop new treatments for patients with diseases related to the immune system, such as arthritis, as well as cancer", says Fredrik Wermeling at the Center for Molecular Medicine (CMM), Department of Medicine, Karolinska Institutet.

Green Listed simplifies work with the CRISPR-methodology

The CRISPR method is based on a system that is found naturally in many bacteria and the method has received a lot of attention in the last few years. A very powerful way to use CRISPR is to in parallel study different parts of the DNA simultaneously, a so called CRISPR screen. "Green Listed" is specifically used to facilitate this type of large-scale studies.

"By implementing the CRISPR methodology in our research, we can now explain phenomena’s we have tried to understand for several years. This is primarily related to CRISPR screen experiments, where we in parallel modify a large number of selected parts of the DNA of isolated cells. The Green Listed software simplifies this process considerably and has been very important for our progress", Fredrik Wermeling says.

DNA is like a cookbook

DNA is an abstract concept researchers often use. Fredrik suggests that a way to think about DNA is that it is similar to a cookbook which cells carry around inside of them.

"The reason for that the cells that make up an individual are different, is that they use different recipes of the cookbook in different ways. Many diseases can to a certain degree be explained by the existence of changes in the DNA of the affected patient. In line with the cookbook metaphor, this could be seen as that one or more recipes in the cookbook have been changed. It is easy to imagine that the end product is radically different if you change a recipe of a cookbook, for example a change from a tablespoon of sugar to a tablespoon of salt. With the CRISPR method, we can quickly make such changes in individual isolated cells and thereby learn about the diseases we study", Fredrik concludes.

The project was financially supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the Wenner-Gren Foundations, the Jeanssons Foundations, BILS (National Bioinformatics Infrastructure for Life Sciences), and the Karolinska Institutet.

Publication

“Green Listed – A CRISPR Screen Tool”

Sudeepta Kumar Panda, Sanjay V. Boddul, Guillermina Yanek Jiménez-Andrade, Long Jiang, Zsolt Kasza, Luciano Fernandez-Ricaud, Fredrik Wermeling

Bioinformatics, 23 November 2016, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw739

Opening hours during the holidays

Registrar's office

Weekdays

Monday-Thursday: 9.00-11.30 and 13.00-15.30

Friday: 9.00-11.30 and 13.00-15.00

Exceptional opening hours

23 December 9.00-12.00

5 Januari 9.00-12.00

Contact

Phone: +46 (0)8-524 865 95

E-mail: registrator@ki.se

Reception in Aula Medica, campus Solna

Weekdays 8.00-17.00

Exceptional opening hours:

23 December 8.00-13.00

5 Januari 8.00-13.00

The Press Office

Exceptional opening hours

Weekdays between Christmas and New Year: 9-17

24 to 26 December: closed

31 December to 1 January: closed

5 to 6 January: closed

Contact

Phone: 08-524 860 77

E-mail: pressinfo@ki.se

Internal post office, campus Solna

Weekdays 7.00-15.00

Exceptional opening hours:

23 December 7.00-12.00

5 Januari 7.00-12.00

University Library

Commuter bus

Urban Lendahl resigns from the Nobel Assembly – here he explains why

Urban Lendahl, Professor of Genetics at the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology at Karolinska Institutet has elected to resign from the Nobel Assembly, citing his actions in the Macchiarini case as the reason.

“I feel I made some bad judgements, so to keep Nobel’s reputation untarnished I have decided to resign from the Nobel Assembly”, Urban Lendahl says.

The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet selects the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. The assembly consists of 50 elected members who are professors at Karolinska Institutet but is independent of the university. Urban Lendahl was elected to the Nobel Assembly in 2001 and was appointed secretary in December 2014.

His errors of judgement concern the Macchiarini affair, which led Professor Lendahl to resign from his position as secretary already in February and take time out from his work for the Nobel Assembly. Swedish Television’s documentary series The Experiment had shown that patients of surgeon Paolo Macchiarini, who had been appointed visiting professor at KI in autumn 2010, fared badly and died following transplants of artificial tracheae. A great many care and research ethics questions were raised and KI decided on an independent review of the case.

Participated as subject expert

Among the errors of judgment that Urban Lendahl now feels he was guilty of concern his actions in connection with two reports of suspected dishonesty in Macchiarini’s research. The reports came from doctors at Karolinska University Hospital and were examined by Bengt Gerdin, Professor Emeritus at Uppsala University. At former Vice-Chancellor Anders Hamsten’s request, Urban Lendahl participated as subject expert at the press conference where KI presented its decision to exonerate Macchiarini from suspicions of misconduct in his research – the very opposite of Bengt Gerdin’s opinion.

“I saw the decision a couple of weeks before it was due to be made public. I read the text but not all the underpinning material and I thought KI had come to the right conclusion. What I didn’t do, that should have been a natural reaction when the decision went against the investigator, was to request that it be referred back or examined by further experts. I acted uncritically but I accepted KI’s line at the time and as a consequence allowed Macchiarini to remain as speaker at a scientific conference that I arranged as late as November 2015.”

The documentary changed everything

“I stuck with KI’s position until the documentaries on Swedish Television that among other things showed operations on patients in Russia who were not terminally ill, that is to say that the operation could not be classified as a vital indication,” Urban Lendahl goes on.

Urban Lendahl is also critical of how he acted when Macchiarini was recruited to KI. Early on in the process, Vice-Chancellor at the time Harriet Wallberg asked him, among other things, what he though about Paolo Macchiarini’s CV. Urban Lendahl told here he felt it looked interesting.

Urban Lendahl was also one of the 14 researchers who signed a document that was submitted to the recruitment committee in support of Macchiarini’s recruitment to KI as visiting professor.

Was asked to fund Macchiarini

Urban Lendahl was also asked by Macchiarini’s future department whether the Program for Strategic Research Areas (SFO) centre StratRegen, which Urban Lendahl led, could contribute financial support to Macchiarini’s offer of recruitment.

“It was then I realised that the recruitment process was far advanced. I approved the request to provide 3.6 million in support and at the time saw no reason to worry in the early phases. This was before the operations. Looking back, It was a bad call and I wish I had gone into his CV in more detail,” Urban Lendahl says.

Why are you taking this decision now?

“It takes time to process tings. During the course of the investigation that followed the documentaries, some things have also emerged that lead me to feel that I made errors of judgment, for example that the hospital investigation showed that it was wrong of the hospital to classify the operations as a vital indication. The Nobel year is also over now and times are les stressful from a Nobel point of view,” he goes on.

What are you hoping to achieve by doing this?

“If you make errors of judgement – even if you have not been in a decision-making position – you should in particular shoulder your responsibilities when organisations like the Nobel Assembly that are based on trust are involved. I am also resigning from Cancerfonden’s research committee for the same reason. For me personally, this is also a way of coming to terms with myself,” he says.

KI finds Paolo Macchiarini and three co-authors guilty of scientific misconduct

Karolinska Institutet has announced its decision on one of several cases of alleged scientific misconduct associated with Paolo Macchiarini. The decision, in brief, means that the lead author and three co-authors of the article have been found guilty of scientific misconduct. For two of the authors, who are more junior, there are mitigating circumstances.

The case relates to the article entitled “Experimental orthotopic transplantation of a tissue-engineered oesophagus in rats” published in Nature Communications in 2014, with Paolo Macchiarini as the lead author. This is the first of several articles by Paolo Macchiarini to undergo re-examination following the decision of the former vice-chancellor to exonerate the researchers from scientific misconduct but censuring the articles for being careless and flawed.

Pursuant to the documentary series “Experimenten” and the resignation of the former vice-chancellor, acting vice-chancellor Karin Dahlman-Wright decided to reopen a number of the cases and demand a statement of opinion from the expert group at the Central Ethical Review Board.

Karin Dahlman-Wright and acting pro-vice-chancellor Henrik Grönberg comment the decision on the first case in an article on today’s DN Debatt page:

“KI’s decision on the matter of scientific misconduct agrees with the pronouncement of the expert group in scientific misconduct at the Central Ethical Review Board (CEPN). KI also shares the CEPN’s view that there are mitigating circumstances surrounding the more junior authors, and that whoever puts their name to a scientific article bears responsibility for it. However, as regards whether all co-authors of a study that has been judged to contain elements of misconduct can be held accountable for the entire published work KI reaches a different conclusion.”

The study in question includes a number of different methods practised by the authors. Since anyone who is an expert on a certain method might well not be in a position to take responsibility for the final compiled results, each author’s responsibility has been assessed individually.

KI finds that Paolo Macchiarini and three of the co-authors had insight into and an overview of the process, either in its entirety or in large part, and are thus to be found guilty of scientific misconduct. The remaining authors contributed in ways that are not judged to constitute misconduct, nor were they in a position to have had insight into or an overview of the whole project.

Regarding penal measures, two senior authors are no longer employed at Karolinska Institutet, so no action in terms of labour law will be taken.

Given that the two junior researchers were in a position of dependency towards their more senior colleagues in the research group and that the process has been very protracted, their circumstances must be considered mitigating. They have therefore been issued with a caution.

International expertise at a Nordic seminar on mice

Comparative Medicine, CM, at Karolinska Institutet is a support and a partner for KI’s researchers in all activities where animal experiments are concerned. CM arranged a conference on 8–9 December on breeding and husbandry of mouse models in laboratory animal science.

“The mouse has come to be the totally dominant mammal model in laboratory animal science and the species will soon have a fully mapped gene catalogue. Bringing together leading international expertise to discuss the latest findings is important for carrying development forward,” says conference host Brun Ulfhake, Director of Comparative Medicine at KI.

Every two years, researchers, breeders and other stakeholders come together at a major seminar within the NorIMM (Nordic Infrastructure for Mouse Models) collaboration, in which KI participates together with University of Bergen, University of Copenhagen and University of Oulu.

Almost 200 delegates took part this time, when international expertise gathered together to discuss the latest research findings. What is the best technique for breeding and preserving mouse models? How can the health and welfare of mouse colonies be secured? How do different diets affect the characteristics of the mice?

One of the aims is to increase quality by refining the methods.

“By doing so we can at the same time achieve a reduction in the number of animals needed in research and experiments. All the issues that are taken up here are important both from the point of view of research quality and from an ethical perspective,” Brun Ulfhake goes on.

Speakers at the conference included Björn Rozell, Chief Veterinarian at KI, Cory Brayton, Professor of Molecular and Comparative Pathobiology at Johns Hopkins University in the USA, and Kristin Lamont, researcher at The Jackson Laboratory, also in the USA.

Rafael Frias, Director of the LAS Education & Training Unit, CM, was responsible for arranging the conference and Johannes Wilbertz, KI Mouse Models coordinator, CM, was a member of the programmed committee.

Text: Karolina Olofsson

What the country’s doctoral students think – comments by the Dean

The Doktorandspegel survey is the third in a series of nationwide surveys focusing on doctoral students’ views of their education. Photo: Istock

Most doctoral students in Sweden are satisfied with the education they receive. Almost 30 per cent, however, feel that their supervision has been so deficient as to jeopardise their research work. This is one of the observations in the latest nationwide survey of doctoral students’ study situation, commented on here by Marianne Schultzberg, Dean of Doctoral Education at Karolinska Institutet.

Good or very good. This is what 86 per cent of doctoral students say about their doctoral education, according to the Swedish Higher Education Authority’s 2016 Doktorandspegeln survey. The findings are based on a questionnaire answered by 4,751 doctoral students, 336 of them from KI, who have completed between three and five terms of their doctoral programme. The response frequency of 47 per cent, however, must be regarded as low.

In the field of medicine and health sciences, which is where most of KI’s doctoral students are to be found, 90 per cent say their overall opinion is good or very good. But the report also shows that there are problems.

In all, 27 per cent of the doctoral students perceive such shortcomings in their supervision that their research work is impeded. In the field of medicine and health sciences, 15 per cent say that their supervisor has shown little or no interest in the doctoral student’s studies.

But KI’s own surveys of its doctoral students have not indicated such serious problems with supervision, says Marianne Schultzberg, Dean of Doctoral Education at KI.

Better figures at KI

“Our own figures look very much better. The vast majority of supervisors do a very good job, but there are some doctoral students who perceive shortcomings. This is sad and we are working on different ways to improve things. We have a compulsory supervisor course for principal supervisors and we’re planning a new procedure for ensuring that the research education environment is appropriate already before the doctoral student is recruited,” she goes on.

The procedure is based on the environment needing to be approved from both a research and a psychosocial perspective before recruiting a new doctoral student.

The report also highlights dissatisfaction with the introduction to doctoral education. KI has compulsory introduction for newly admitted doctoral students that is currently under review to find ways to improve it.

Two out of ten get no follow-up

The Higher Education Ordinance states that doctoral students’ individual study plans are to be followed up on a regular basis. In spite of this, two out of ten doctoral students in the field of medicine and health sciences say that their study plan has not been followed up during the current year. KI recognises the problem and the situation is expected to improve when electronic individual study plans are introduced next year. A reminder will appear in the programme when the time comes to update a study plan.

Roughly a quarter of the doctoral students say that their research findings have been used without their being cited as the author or originator. It is not clear, however, what kind of illicit utilisation occurs most often or in what fields. KI does not ask about this in its surveys of doctoral students in the field of medicine and health sciences and in Marianne Schultzberg’s opinion it is difficult to draw any definite conclusions from the findings.

The report shows that 11per cent of the doctoral students in the field of medicine and health sciences have experienced some form of discrimination, gender being the most common reason.

“It’s too many. We’ve seen this in our own surveys and we’ve discussed discrimination with every department’s management. We’re hoping that our new procedure for preparing for a doctoral student recruitment will prevent doctoral students being admitted to environments that are not suitable,” she says.

Shadow doctoral students

Being a shadow doctoral student, meaning participating in a doctoral programme without being formally admitted, was most common in the field of medicine and health sciences. 55 per cent of those who answered the questionnaire had been in that situation, which can be uncertain and insecure. At KI, however, Marianne Schultzberg thinks that these are mainly people who work in care and who are beginning a research project at their place of work.

“But it’s naturally important to all the time make sure that there aren’t any students working in research projects who lack economic support and who have not been formally admitted,” she says.

Despite the shortcomings, 84 per cent of the doctoral students in medicine and health sciences nonetheless say that they would probably or definitely embark on doctoral studies again if they were choosing today.

Text: Sara Nilsson

About the Doktorandspegel survey: The 2016 Doktorandspegel survey is the third in a series of nationwide surveys focusing on doctoral students’ views of their education. The two previous surveys were conducted by the Higher Education Authority’s predecessor the National Agency for Higher Education and published in 2003 and 2008.

The new Ethical Council will have a broader remit

The new members of the Ethical Council will be appointed early next year according to the decision of the Vice-Chancellor. Photo: Istock

Karolinska Institutet’s Ethical Council, which previously had an advisory role under the Vice-Chancellor, was dissolved in March in the wake of the Macchiarini case. A new Ethical Council is now to be formed. The new council’s remit will first and foremost be strategic. Matters concerning misconduct will at the same time be removed from the council’s area of responsibility.

“Karolinska Institutet is a university where ethical questions are to be in focus. Recent events have proven the importance of KI’s work regarding ethical questions and our basic values,” said newly appointed acting Vice-Chancellor Karin Dahlman-Wright in March this year.

The Ethical Council was dissolved and its work suspended. Shortly thereafter, the new acting Pro-Vice-Chancellor, Henrik Grönberg, was asked to make a review and draw up a new remit for the Ethical Council.

The result: The new Ethical Council is not to have an operative function – matters concerning misconduct are not to be investigated by the Ethical Council, which is instead to be given a strategic role.

Some cases of misconduct were previously dealt with by the Ethical Council, others by the Vice-Chancellor directly. Following the Macchiarini case, several cases of misconduct have needed to be scrutinised again.

“They are such serious cases that a good structure is needed,” Henrik Grönberg says.

New procedure for cases of misconduct

Before the end of the year he will present the new procedure for handling cases of suspected professional misconduct in research.

A nation-wide study is being conducted at the same time on the government’s initiative, but new legislation on cases of misconduct cannot come into force until 2019.

“We can’t wait until then,” Professor Grönberg goes on.

The Ethical Council will instead now be assigned to raise complex issues that need detailed investigation and the council itself will decide what to discuss. KI staff members will also be able to contact the council.

Their questions might for example concern KI’s stance on co-authorship, or on research conducted by KI employees or KI associates in other countries, or how genetic information that emerges from research studies is to be handled.

The Ethical Council is to be able to problematise and discuss issues in order to then provide guidance as to what is right and proper.

Both KI staff and external members

Another important change to the Ethical Council’s remit is that KI’s Pro-Vice-Chancellor will be a member of the council. This will allow us to get support for ethical issues in the organisation and legitimise the council’s strategic importance.

The other members will be appointed by the Vice-Chancellor based on nominations by staff and students. Half of the members will be KI employees, the other half will come from outside, and have competence in the fields of law, press/media or politics. The council will have between eight and ten members in all.

The result that Henrik Grönberg is hoping to achieve is both that the Ethical Council will be able to make recommendations concerning ethical questions and that the Pro-Vice-Chancellor will be able to ensure that the council’s questions and responses permeate the organisation as a whole.

A further task for the Ethical Council will be to arrange seminars that open up for discussions on complex questions.

One of the models for Karolinska Institutet’s new ethical council was the one at Lund University, where newly appointed acting Pro-Vice-Chancellor, Anders Ekbom, is an external member.

Text: Madeleine Svärd Huss

KI researcher receives grant on basis of top ERC assessment

Vicente Pelechano Garcia at the Department of Microbiology, Tumour and Cell Biology is one of two researchers to be awarded a Swedish Foundations’ Starting Grant. The grant is arranged jointly by five private research foundations and is awarded to young research group leaders who achieved a top grade and proceeded to the interview stage of their ERC Starting Grant application but did not make it all the way.

As a recipient of this Swedish start-up grant, Vicente Pelechano Garcia is guaranteed approximately EUR 1.5 million for five years on condition that every year he applies for funding from the European Research Council (ERC). Should the ERC approve his application the Swedish grant will be cancelled.

The five foundations are: The Erling-Persson Family Foundation, the Kempe Foundations, the Ragnar Söderberg Foundation, the Bank of Sweden Tercentary Foundation and the Olle Engkvist Byggmästare Foundation. The foundations base their evaluations of current projects solely on those of the ERC.

The research applications to the ERC “are some of the most detailed currently composed in Sweden. It is a widely known fact that the quality of all those that proceed to interview is exceptionally high. The expert assessment is of the highest class. In today’s research community, an ERC grant is the most meritorious form of financing available. By making available the Swedish Foundations’ Starting Grant we hope to capture young researchers at the forefront of European science and provide them with sustained support for their research,” write the foundations in a joint press release.

The other recipient of the Swedish Foundations’ Starting Grant is Cristian Bellodi at Lund University. Dr Pelechano Garcia was also recently made a Wallenberg Academy Fellow.

Research on galanin can result in new drugs for depression

Depression inflicts a large number of human beings under their lifetime. In addition to suffering and a considerable risk for suicide, the disease is associated with major cost for Society.

Different types of treatment of depression are available. Often it is pharmacological, for example with SSRIs, e.g. Prozac. Even if this treatment is successful in around 60% of patients, there are problems with resistance, side effects and late onset of the therapeutic effect.

Against this background researchers at Karolinska Institutet are searching for new targets for development of improved antidepressants. Among targets are receptors for neuropeptides, a large group of neurotransmitters. Galanin is a 29/30 amino acid long neuropeptide that acts via three receptors, GalR1-3.

Studies show an anti-depressive effect

Galanin, which was purified from porcine intestine, was discovered more than 30 years ago by Viktor Mutt and his PhD student Kazuhiko Tatemoto at KI. This peptide has since then been studied with focus on depression by several groups at KI and Stockholm university. Extensive animal experiments suggest that the GalR1 antagonist could have antidepressive effect.

Swapnali Barde and collaborators have now investigated to what extent the results from animal experiments are relevant for humans. Five regions were studied in post-mortem brains from depressed women and men that had committed suicide and from controls.

"We use three methods for analysis of galanin and the three receptors: qPCR to measure levels of transcript (mRNA), prosequencing to measure DNA methylation (epigenetic changes) and radioimmunoassay, the latter however only to measure concentrations of galanin", says one of the authors, Tomas Hökfelt.

Results show a difference between sick and healthy brains especially in the frontal lob and in two nuclei in the lower brain stem, various anterior cingulum was not affected at al. Furthermore, it was especially the transmitter cells, that is galanin and GalR3 that show changes. Both were upregulated in the brain stem nuclei and downregulated in the frontal lobe.

"At the same time the methylation was changed in the opposite direction, which is in agreement with a theory that methylation suppresses synthesis. The changes were seen both in women and men", Tomas Hökfelt continues.

Fewer side effects expected

GalR3 coexists both with noradrenalin and 5-hydroxytryptamin in separate nerve populations in the nuclei mentioned above in the lower brain stem. GalR3 is an inhibitor receptor that slows down activity in these nerve cells and in this way reduces release of NA and 5-HT in the forebrain. Since the transcript for both galanin and GalR3 are upregulated, these likely results in reduction in activity of these two monoamines in the forebrain in depression. A GalR3 antagonist could as medicine thus possible have an antidepressant effect by inhibiting ‘the break’.

"The end result is similar to what SSRIs and similar medicine cause, namely to increase the brains content of 5-HT and NA – but via a completely different mechanism. The expectation is that a GalR3 antagonist also would act faster, that is without delay, as well as have fewer side effects", concludes Tomas Hökfelt.

Publication

"Alterations in the neuropeptide galanin system in major depressive disorder involve levels of transcripts, methylation, and peptide"

Swapnali Bardea, Joelle Rüegg, Josée Prud’homme, Tomas J. Ekström, Miklos Palkovits, Gustavo Turecki, Gyorgy Bagdy, Robert Ihnatko, Elvar Theodorsson, Gabriella Juhasz, Rochellys Diaz-Heijtz, Naguib Mechawar, Tomas G. M. Hökfelt

PNAS. Published online 9 December 2016.doi: 10.1073/pnas.1617824113

Pokemon Go only slightly improves physical activity among adults

Among young adults in the US, playing Pokemon Go was associated with increased physical activity, but the effect was moderate and not sustained beyond 6 weeks, finds a study from Harvard University and Karolinska Institutet that was published in The BMJ Christmas issue.

Pokemon GO is an augmented reality game in which the player search real world locations for cartoon characters appearing on their smartphone screen. It has been downloaded over 500 million times since its launch in the summer of 2016. It has been suggested that the game can increase physical activity and promote public health, because it incentivizes walking. However, these claims are based on anecdotal evidence.

Therefore, researchers from Harvard University in the US, and Karolinska Institutet investigated whether playing the game had any effect on physical activity among young adults in the US. They conducted an online survey of 1,182 participants, aged 18-35, who used iPhone 6 series smartphones.

Almost half of the participants were on a high level

Of the participants, 560 (47.4 %) reported playing Pokemon GO at a “trainer level” of 5 or more, which is reached after walking for around two hours. Automatically recorded step count data were obtained from participants’ iPhones and used to estimate the change in daily steps after installation of the game.

Results show that the daily average steps for players during the first week of installation increased by 955 additional steps, and this would translate into 11 minutes of additional walking daily - assuming steps of 0.8 m at a pace of 4 km/h/. This is around half of the WHO recommended minimum of 150 minutes weekly.

Effects were lost after six weeks

The number of steps gradually decreased over the following five weeks, and by the sixth week after installation, the number of daily steps had gone back to pre-installation levels.

"Because the steps were only recorded when the iPhone was carried, the effect of the game on physical activity may have been overestimated, and the study population was not representative of the general US population", says Peter Ueda, researcher at the Department of Medicine at Karolinska Institutet and one of the authors of the study.

"The results show that the public health impact of Pokemon Go is likely to be limited in our study population of young adults in the US", Peter continues.

PokemonGo can appeal to individuals with interrest in computers

There might be individuals who sustain an increase in physical activity through Pokemon GO. Football or line dance might also have small effects on physical activity in the broad population if introduced as a new activity in adult age, but they probably work fine for individuals who enjoy them.

"It can also be speculated that Pokemon Go can appeal to groups who are not likely to engage in more established types of physical activity, such as individuals with a strong interest in computers", Peter Ueda says. "In addition, the relationship between the game and physical activity might differ in children who were not included in the study. But to suggest that Pokemon Go would be an important and sustainable factor for tackling the global problem of physical inactivity, however, might be a bit optimistic."

Publication

"Gotta catch’em all! Pokémon GO and physical activity among young adults: difference in differences study"

Howe KB*, Suharlim C*, Ueda P*, Howe D, Kawachi I, Rimm EB. (*Shared first authorship)

BMJ, published online 13 December 2016. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i6270

Professor Emeritus Georg Klein passed away

Georg Klein passed away on 10 December. Photo: Gunnar Ask

Georg Klein has died. Born into a Hungarian-Jewish family in Budapest in 1925, as a 22-year-old medical student he fled to Sweden to escape the Soviet occupation. He was Professor Emeritus in Tumour Biology at Karolinska Institutet and up to the last was an active researcher at the Department of Microbiology, Tumour And Cell Biology, MTC.

Last year he celebrated his 90th birthday together with his wife and colleague Eva Klein, Professor Emerita in Tumour Biology. The occasion was commemorated among others by students and colleagues with a scientific symposium that was attended by cancer researchers from around the world.

“It is with great sadness that I have learned of the passing of a brilliant researcher, doctor and role model. Together with his wife Eva, Georg Klein leaves behind an enormous contribution to Karolinska Institutet, the global research community and tumour biology. My thoughts today go first and foremost to his family and to all the colleagues who worked so closely with him,” says Karin Dahlman-Wright, Acting Vice-Chancellor at Karolinska Institutet.

After completing his medical studies and a PHD degree, Georg Klein was awarded a personal professorship in 1957. A donation from Riksföreningen mot cancer (now Cancerfonden) enabled him and his wife to build up the Department of Tumour Biology at Karolinska Institutet, which was later to become a world-leading centre in tumour biology for four decades. This interdisciplinary department combined genetics, infection models, immunology and animal models to come to grips with the problem set associated with cancer.

Georg and Eva Klein are responsible for a great many important discoveries in cancer research. In the 1960s, they laid the foundation for modern tumour immunology that has led to today’s successes in immunotherapy against cancer. Georg Klein also proved that the genetic make-up of normal, healthy cells can suppress cancer cells’ malignant behaviour. He also conducted extensive studies of the Epstein-Barr virus and its role in lymphoma and other forms of cancer. In recent years he took an interest in the converse problem: Why is it that two thirds of all people do not develop cancer?

He has taught an immense number of doctoral students and young researchers who are now doing their work all over the world. Georg Klein’s capacity was legendary and he seemed to make use of every available minute to do something meaningful. When he was to be interviewed a while ago, he had hardly greeted the reporter before telling him to get on with the questions. On the subject of death and the meaning of life, he had this to say: “It’s the time we’re given that makes life so valuable. The great human tragedy is that people seek the meaning of life with a capital M. Personally, I’m happy with my small meanings: the people I love and my work.”

For a wider audience, Georg Klein became known as an author after his first book was published in 1984, with both a philosophical-humanistic and a popular-scientific thrust. One of his best-known books is perhaps Om kreativitet och flow (On creativity and flow), Bromberg, which he co-authored. Achieving flow was a strong driving force for Georg Klein. The book first appeared in 1990 and a new edition was published in 2012. In recent years he published Jag återvänder aldrig. Essäer i Förintelsens skugga (I will never return. Essays in the shadow of the Holocaust), Albert Bonniers Förlag, 2011, about anti-Semitism in Klein’s former home country Hungary.

As most recently as spring this year he was awarded the Gerard Bonnier Essay Prize for what was to be his last book: Resistens (Resistance). Thoughts on resistance, Albert Bonniers Förlag, 2015, “for a healing authorship where the encounter between measurable natural science and knowable humanism reflects the art of living”.

Georg Klein won innumerable prizes and awards over the years for his work in cancer research. He was a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Karolinska Institutet’s Nobel Assembly between 1957 and 1993, and a member of the National Academy of Sciences in the USA.

To commemorate the couple’s 80th birthdays in 2005, their research colleagues at MTC set up The Georg and Eva Klein Foundation. The aim of the foundation is to support research on tumour biology, cell biology, infections and cancer in the spirit of Georg och Eva Klein.

From his retirement in 1993 until his death, Georg Klein was a research team leader at the Department of Microbiology, Tumour And Cell Biology, MTC, at Karolinska Institutet.

Georg Klein was 91.

Funding from ERC to track cells by using DNA origami

Congratulations to Björn Högberg, Associate Professor and group leader at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, who was recently awarded the ERC Consolidator Grant from the European Research Council, for the project 'Cellular Position Tracking Using DNA Origami Barcodes'. The grant is aimed at young research leaders and provides 2 million euros over a five year period.

What are you going to do?

"We are developing a new system for tracking cells in experiments with transcriptomics, to map the activity of different genes at a given time point. Many labs, in particular at KI, now do transcriptomics on single cells. One problem is that, in most cases we do not know exactly where the individual cells have been located in the tissue. By making a sort of address tag of a nanostructure made of DNA, known as DNA origami, which can be read by both microscopy and sequencing, we hope to be able to correlate the transcriptome to the exact original location of the cell in the tissue."

What does it mean for you to get this kind of funding?

"It is big. ERC is known to provide funding for the best research. It is a confirmation that we are doing good research. It is also a much-needed addition to the research group's finances and will allow us to immerse ourselves in research that we otherwise might not have dared to do."

Do you have any advice for others applying for ERC?

"Don’t hesitate to apply and don’t just apply once. This was the second time I applied and the first time I was a little burnt by the whole process so it took two years before I had the energy to apply again. It feels as though the chances of getting the grant are slim. You have to be lucky with the reviewers and with the panel, so the more times you have the energy to apply the greater your chance will be."

How have you celebrated?

"We had a small party in the lab when I found out about it. We will also go out to eat dinner together, since it is really thanks to all my talented lab members that this finally became a reality. I especially want to mention my PhD student Ferenc Fördös, who has been integral in conducting the preliminary work."

Star-gazing with Nobel Laureate Yoshinori Ohsumi in Aula Medica

There was not an empty seat in Aula Medica when Yoshinori Ohsumi gave his Nobel lecture that was filled with treats for anyone interested in research. He spoke for an hour about the 27 years of research that culminated in him receiving the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

It was under a cloudy December sky that the queue slowly wound its way into Aula Medica and filled every seat. When the star of the evening, Yoshinori Ohsumi, finally appeared, a thousand people watched him make his way to the stage, along with not a few wide-eyed cameras.

Before the lecture, Karin Dahlman-Wright, KI’s acting Vice-Chancellor, had welcomed the audience saying that today “We celebrate science”. And that’s precisely what this years winner of the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine proceeded to do.

“I think every researcher is a product of his or her time,” he began in his customary quiet manner before continuing with a brief summary of his background.

I spent a great deal of time outside, collecting insects and observing the stars.

His journey through life began in Japan, where he was born just before the end of the Second World War. His early years were very difficult. His mother suffered from tuberculosis and was bed-ridden for long periods. He himself was undernourished as a result of the food shortage.

The seeds of his research, curiosity and an interest in nature, were sown already at that stage of his life.

“I spent a great deal of time outside, collecting insects and observing the stars, he told the audience.

After this glimpse into the Nobel Laureate’s private life, the lecture plunged into the world that Yoshinori Ohsumi was the first one to explore – autophagy’s molecular landscape. But first he explained, against a background of images of trees and rice fields in different seasons, why the degradation and recycling process is of interest.

“Nature is in a state of constant change and degradation is not destructive but a precondition for building something new. The proteins that are formed in our body do not come primarily from the food we eat but from other proteins in our body that have been degraded and recycled,” he said.

In 1988, when he had found his research focus, he was finally given the opportunity to set up a laboratory of his own.

“It was just me,” he said and raised a few laughs.

For me, these 27 years have been a winding path with many unexpected coincidences and encounters.

He spent a lot of time in his lab, “more than anyone else”, staring at yeast cells through a microscope. But in the vacuoles, the organelles where he believed degradation might take place, there didn’t seem to have anything at all going on. His breakthrough came when he managed to shut off a number of genes that are necessary for the process and thus get parts of the machinery to accumulate and become visible.

Then he could begin to put the puzzle together – 15 genes were identified, each with its own research history. Yoshinori Ohsumi and his team were gradually able to identify the various components in the process in the form of proteins and explain their functions.

He ended his lecture by showing a graph of the number of publications on the subject of autophagy. The field simmered along for a long time until it suddenly exploded, which is connected to the fact that the process proved to be important in a great many diseases and physiological processes.

“For me, these 27 years have been a winding path with many unexpected coincidences and encounters. I have always been driven by intellectual inquisitiveness and I never though autophagy would be of such great importance. I would like to thank all the researchers who have contributed to that,” he said and was given a standing ovation.

Text: Ola Danielsson