KI News

The Vice-Chancellor’s comments on the board’s decision

At an extraordinary meeting held on 4 February, the Karolinska Institutet University Board (Konsistoriet) made a number of decisions in the matter of researcher Paolo Macchiarini. Here, Vice-Chancellor Anders Hamsten comments on these decisions.

“I welcome the manifest support the board gives me,” he says. “I intend to continue as vice-chancellor of Karolinska Institutet with full force and energy, and to execute my responsibility in this situation in the best possible way.”

“The decisions taken by the board are fully in line with what I myself believe must be done now.”

Anders Hamsten has no further comment.

Read the University Board’s press release here

The Board initiates external investigation

The Karolinska Institutet University Board (Konsistoriet) has today announced its decision to arrange an external investigation into the “Macchiarini case”. The process will cover events taking place at Karolinska Institutet (KI) since the recruitment of surgeon Paolo Macchiarini as visiting professor in 2010 until the present day, when he has been notified by the Vice Chancellor that his contract will not be extended. The University Board deems such an inquiry to be an important part of restoring the confidence of the public, the scientific community, staff and students in the university.

The University Board is charged by the Higher Education Act with ultimate responsibility for the university’s business, which includes establishing and auditing processes for internal control, risk management and general management. The University Board is also vested by the Higher Education Ordinance with a critical role in the appointment of the vice-chancellor and the responsibility of regularly ensuring that the vice-chancellor and the senior managers he or she appoints do not fail in their competence and judgement.

The investigation will be led by a highly experienced lawyer, who will subsequently be writing the final report. Well-qualified medical researchers, ideally not from Sweden, should assist in this work. The person tasked with leading the work will decide on who is to take part in the investigation and on what resources will be needed to bring the inquiry to a satisfactory conclusion. KI’s internal audit office, which answers direct to the University Board, will also be a resource available to the investigation.

It is hoped that the investigative team will be formally appointed next week.

The decision-making rights of the university board are defined by chapter 2, section 6 of the Higher Education Act. Since the board may not rule on issues requiring scientific competence, it may not, for example, decide on whether KI shall conduct research on synthetic trachea or sit in judgement on suspected scientific misconduct or overrule decisions on such.

The investigation will cover that which falls within the University Board’s sphere of responsibility, and will thus not be examining matters of a medical-scientific nature. Issues that that external investigation should consider are:

Was any law broken or other formal transgression committed on Macchiarini’s recruitment or later during his period of employment at KI?

Were adequate inquiries made in connection with his recruitment?

Was sufficient effort made at a departmental and university management level to ensure that Macchiarini’s activities were conducted in a proper scientific manner with due respect to research ethics?

Has his research been documented in a manner consistent with the rules and praxis in effect at KI?

Has the division of responsibility between KI and Karolinska University Hospital been sufficiently clear, and has their collaboration been adequate from a research and clinical perspective?

Has the chain of responsibility from department to Vice-Chancellor and the University Board been sufficiently effective?

Was anything – or enough – done to ensure that Macchiarini’s extramural activities complied with KI’s scientific and ethical requirements?

Were the allegations of scientific misconduct levelled against Macchiarini handled correctly?

Why was Macchiarini’s employment contract extended in 2015 in spite of the obvious doubts there were about his activities?

The University Board would like the investigation to draw up recommendations on, for example, amendments to the internal rules and control system, should this be deemed warranted. It also welcomes proposed amendments to the national regulations for forwarding by the University Board to the relevant government offices.

It is the University Board’s hope that the investigation will be concluded by the summer, but if a longer time is needed to ensure a high standard of inquiry, this will take precedence.

The University Board has full confidence in Vice Chancellor Anders Hamsten and has urged him to remain in office during the investigation. Whether the outcome of the investigation will lead the board to change its stance in this respect is not a matter for speculation at present.

Related: The Vice-Chancellor’s comments on the board’s decision

Decision about Paolo Macchiarini’s employment at Karolinska Institutet

Karolinska Institutet’s Vice-Chancellor has decided today that researcher Paolo Macchiarini’s employment will not be extended when his current contract expires.

The head of Macchiarini’s department has been instructed by the Vice-Chancellor to ensure that, until 30 November 2016, Macchiarini uses his working hours to phase out the research he has conducted at KI. The head of department is also responsible for ensuring that the work of his research group is dismantled.

Related content: "Comment on the TV documentary 'Experimenten'".

Minority of cancer cells affect the growth and metastasis of tumours

New research shows that a small minority of cancer cells in neuroendocrine tumours of the pancreas contribute to the overall growth and metastasis of the tumour. This discovery was made by a research group at Lund University, in collaboration with researchers at Karolinska Institutet.

The findings are of fundamental biological importance for the understanding of the different functions of cancer cells, and are now published in the scientific journal PNAS.

Cancer emerges when mutations and other genetic alterations shut down the control system for growth that can normally be found in our cells. All cancer cells in a tumour were previously believed to have the same potential to grow and metastasise, but recent studies show that tumours are comprised of several types of cancer cells with different genetic alterations.

“The fact that there are so many different types of cells within a single tumour could explain why only some cancer cells are able to metastasise, and why some patients experience recurrence of their tumorous disease, despite having undergone extensive treatment”, explains Professor Kristian Pietras at the Department of Laboratory Medicine at Lund University, also affiliated to Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics.

Neuroendocrine tumours, NET, is a generic name for a type of hormone-producing tumour. In their study, the research group showed that in neuroendocrine tumours of the pancreas, a small minority of tumour cells significantly contributed to the overall growth of the tumour.

Kristian Pietras is the Göran and Birgitta Grosskopf Professor at Lund University. The current study is supported by a Consolidator Grant from the European Research Council, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Society, the STARGET consortium (a Swedish Research Council Linnaeus network), BioCARE, and Lund University.

Learn more in a press release from Lund University

Publication

Functional malignant cell heterogeneity in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors revealed by targeting of PDGF-DD

Eliane Cortez, Hanna Gladh, Sebastian Braun, Matteo Bocci, Eugenia Cordero, Niklas K. Björkström, Hideki Miyazaki, Iacovos P. Michael, Ulf Eriksson, Erika Folestad, and Kristian Pietras

PNAS, published online before print February 1, 2016, doi:10.1073/pnas.1509384113

Imagined ugliness can be treated with internet-based CBT

Imagined ugliness, or body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) as it is known, can be treated with internet-based CBT, according to a recent randomised study, the first of its kind ever conducted. The new treatment, which is published in the British Medical Journal, has been developed by researchers at Karolinska Institutet and has the potential to increase access to care for sufferers of BDD.

People suffering from BDD have a preoccupation with perceived flaws in one’s physical appearance, despite looking normal. However, even though the diagnosis is associated with an elevated risk of suicide, higher rate of sick leave and considerable distress, BDD has long been neglected by the care services, leaving sufferers struggling to find the help they need.

In order to increase access to therapy, a new type of internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has been developed and tested in the largest treatment study to date. After twelve weeks’ of treatment, one in every three patients no longer met criteria for a diagnosis of BDD.

“Our results show that internet-based CBT outperformed supportive therapy, and that its therapeutic effect is fully comparable with that achieved by conventional CBT,” says the study’s first author Jesper Enander at Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Clinical Neuroscience.

A majority of the 94 patients included in the study had been suffering from BDD for many years and had had previous contact with the healthcare services. One in five had undergone one to six plastic surgery operations trying to “fix” perceived flaws in their appearance. For the study, the group was randomly assigned to two forms of therapy: internet-based CBT or supportive therapy. Those assigned to this latter control group were later offered CBT.

Greatly reduced symptoms

Immediately after the therapy programme ended, half of the people in the CBT group showed greatly reduced symptoms. One third were completely cured. CBT also improved the participants’ quality of life and reduced depressive symptoms. Of the participants who had major depressive disorder at the start of the study, half were no longer depressed at the end of the study.

The researchers hope that the treatment will eventually be made generally available, so that more BDD sufferers can get access to treatment that works.

“Many BDD suffers receive no treatment at all, partly because the condition is relatively unknown within the healthcare services but also because people with the disorder tend not to seek treatment out of fear that they’ll be dismissed as superficial or not be taken seriously”, says principal investigator Christian Rück at Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Clinical Neuroscience. “Most of the study participants also said it was the possibility to do the therapy online that made them seek any help at all in the first place.”

The study was financed by ALF funds from Karolinska Institutet and the Stockholm County Council, the Swedish Research Council and the Swedish Society of Medicine.

View our press release about this study

Publication

Therapist-guided Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: A single-blind randomised controlled trial

Jesper Enander, Erik Andersson, David Mataix-Cols, Linn Lichtenstein, Katarina Alström, Gerhard Andersson, Brjánn Ljótsson, Christian Rück

British Medical Journal, BMJ 2016;352:i241, online 2 February 2016, doi: 10.1136/bmj.i241

No link between subcortical brain volumes and genetic risk for schizophrenia

Common genetic variation associated with risk for schizophrenia is not linked to the volume of regions below the cerebral cortex in the brain, according to a large international study led from Karolinska Institutet and University of North Carolina School of Medicine in the United States. This proof-of-concept study, published in Nature Neuroscience, provides a roadmap for future research into possible associations between brain volume measures and known genetic risk factors.

Over the last decade, important contributions to our understanding of schizophrenia have come from two different types of studies.

Neuroimaging studies have found that certain parts of the brain, such as the hippocampus and amygdala, are smaller in people with schizophrenia – a devastating psychiatric illness with high heritability. At the same time, large genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which analyzed gene sequences from thousands of people, have found evidence suggesting that schizophrenia arises from the combined effects of many genes and not from a defect in any single gene.

Combining these two approaches was a logical next step. A new study led by Patrick F. Sullivan, MD, FRANZCP, a researcher and professor at both the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, US, and Karolinska Institutet, evaluated the relationship between common genetic variants implicated in schizophrenia and those associated with subcortical brain volumes.

The study, which is a large-scale, global collaboration involving nearly 600 researchers from more than 350 institutions, was published online ahead of print by the journal Nature Neuroscience.

“In our study, we integrated results from common variant studies of schizophrenia and volumes of several brain structures,” Sullivan said. “We did not find evidence of genetic overlap between schizophrenia risk and subcortical volume measures, either at the level of common variant genetic architecture or for single genetic markers.

Roadmap for future studies

“However, this proof-of-concept study defines a roadmap for future studies investigating the genetic covariance between structural/functional brain phenotypes and risk for psychiatric disorders,” Sullivan said.

At UNC, Sullivan is Yeargan Distinguished Professor of Genetics and Psychiatry and Director of Psychiatric Genomics. At Karolinska Institutet he is Professor of Psychiatric Genetics in the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics. He is also the founder and the lead principal investigator of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, the largest consortium in the history of psychiatry.

This research was supported by several funding bodies and medical companies, including the US National Institutes of Health, the European Union’s Seventh Frame Programme, the Welcome Trust, UK, and the Swedish Research Council (full list in the article). Researchers from institutions in the following countries contributed to the study: Austria, Australia, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, China Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Israel, Japan, Lithuania, Netherlands, Nigeria, Norway, Poland, Russia, Sweden, UK, and USA.

Our press release about this study

Publication

Genetic influences on schizophrenia and subcortical brain volumes: large-scale proof of concept

Barbara Franke, Jason L Stein, Stephan Ripke et al.

Nature Neuroscience, online 1 February 2016, doi:10.1038/nn.4228

Two KI researchers receive ERC Consolidator Grants

Weimin Ye and Gonçalo Castelo-Branco, both researchers at Karolinska Institutet, have been awarded ERC Consolidator Grants in the 2015 call for applications. The grant, which is for up to 2.75 million euro, is for researchers who have recently started a research group and who are seeking to enhance their role as principal investigator.

Weimin Ye at the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics researches the causes of tumours in the airways and gastrointestinal tract, such as the part played by the bacterial flora in the development of stomach cancer.

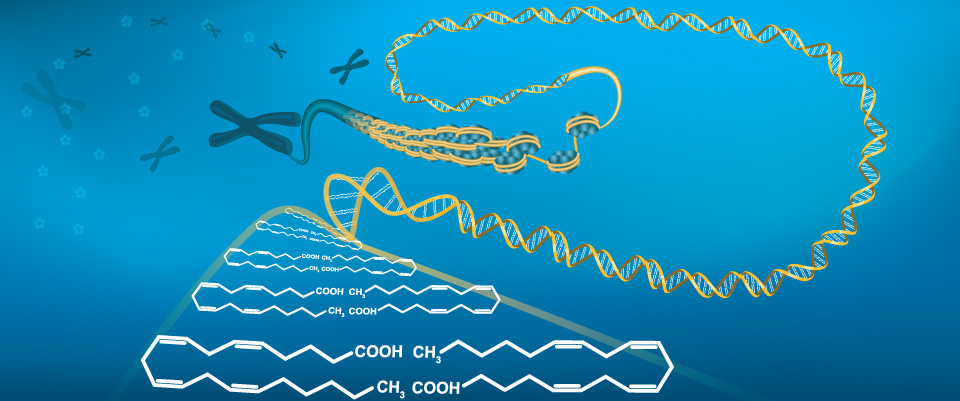

Gonçalo Castelo-Branco at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics focuses his research on how molecular mechanisms regulate transitions between epigenetic states in stem cells and precursor cells in the nerve system and other organs.

Also: KI researchers awarded ERC Starting Grants in the 2015 call for applications (in Swedish only).

Press release on ERC Starting Grant.

Comment on the TV documentary ”Experimenten”

Swedish Television (SVT) has made three programmes investigating Professor Paolo Macchiarini, a researcher employed at KI. The programmes contained information that was unknown to the university management, which means that the inquiry into suspected scientific misconduct might be reopened against Professor Macchiarini.

“My conclusion is that we need to examine and evaluate the claims made in the documentary, and will be reopening the inquiry if there is reason to do so,” says Karolinska Institutet’s vice-chancellor, Anders Hamsten.

Professor Hamsten reacted strongly to the material that was shown in the SVT documentary and that concerns operations Professor Macchiarini had performed in Russia.

“We’ve seen footage in SVT’s documentary that is truly alarming, and I empathise deeply with the patients and their relatives. Many of the circumstances, as portrayed in the programme, are wholly irreconcilable with KI’s values and with what we expect of our employees. If what the programme claims about patients being tricked or talked into undergoing surgery on dubious grounds is true, it is naturally altogether inacceptable.”

Professor Macchiarini is currently on a one-year research contract with Karolinska Institutet, and it is too early to say what will happen to his employment status.

“The information presented in the SVT documentaries and other media are naturally very grave, but we must get to the bottom of this ourselves, and not simply judge someone based on reports in the media,” says Professor Hamsten.

Professor Macchiarini was on a part-time contract at Karolinska Institutet from 2010 to 2015, and had approved extra-occupational activities in Krasnodar, Russia. Although the university management knew that he had operated and researched there, the information that has emerged in the documentaries on the ethical nature of these operations is new to Professor Hamsten.

“The three patients on whom Paolo Macchiarini operated at Karolinska University Hospital in 2011 and 2012 were seriously ill and judged to have little time left to live. We assumed that the same was true for the patients operated on in Krasnodar.”

Karolinska Institutet does not allow secondary occupations that are undermining confidence, and given the way Macchiarini’s activities in Russia have been described in the documentary, they would never have been approved, explains Anders Hamsten.

“KI will now see if the way secondary occupations are reported at the university needs revising so that we may more readily judge the potential harm they can do to our reputation.”

In 2014, Karolinska Institutet opened an extensive inquiry against Professor Macchiarini for suspected scientific misconduct. In his verdict in August 2015 vice-chancellor Anders Hamsten concluded that while on some points Paolo Macchiarini did not meet the high standards set by KI and the scientific community, it does not qualify as scientific misconduct. KI’s inquiry did not concern matters relating to healthcare practices or medical ethics regarding the operations conducted at Karolinska University Hospital, but only whether the articles correctly stated the facts at the time of publication.

One outcome of this inquiry was that KI and Karolinska University Hospital began a review of the boundary separating healthcare and research.

The division of responsibility between KI and Karolinska University Hospital is such that the medical and therapeutic responsibility for the patients operated on in Sweden falls under the remit of the hospital. Since 2013, no such operations have taken place in Sweden, and the last one in Russia was in June 2014.

On 5 January, Vanity Fair published an article in which it was claimed that Professor Macchiarini gave false information in his CV on his recruitment at KI in 2010. This information is currently under investigation by Karolinska Institutet.

“As an academic institution, Karolinska Institutet’s role is to create new knowledge, and that takes creative, innovative researchers. On recruiting Paolo Macchiarini in 2010, the university made the normal assessments and checks that, in the vast majority of cases, provide an accurate guide. For many years, KI has endeavoured to build up knowledge in the new field of regenerative medicine, and at the time, employing Professor Macchiarini was deemed the right thing to do.

Comment from Karolinska University Hospital (in Swedish)

Karolinska Institutet and Ferring Pharmaceuticals signs collaboration agreement

Ferring Pharmaceuticals and Karolinska Institutet announce today that a collaboration agreement has been signed for the establishment of a research center exploiting the human microbiome. The programme will be fully funded by Ferring Pharmaceuticals and governed by a joint steering committee.

The proposed project focuses on therapeutic areas where Ferring has extensive expertise. Karolinska Institutet has a deep understanding of the human microbiome. Parts of the research will be carried out at the Science for Life Laboratory (SciLifeLab) that provides access to a broad technical platform for studying complex microbiological communities in well-defined human material.

The collaboration between the two partners form a solid foundation for the ambition of a better understanding of the contribution of the human microbiome to physiology and pathophysiology and opens opportunities for development of novel therapies. The research will be led by Professor Lars Engstrand, Karolinska Institutet, whom will serve as director. The center will further establish an internationally competitive infrastructure with focus on translational research in the microbiome field set up to develop a comprehensive mapping of the human microbiome in health and disease.

“The strength of the center lies in its well-established network between scientists representing different competence, said Lars Engstrand, Professor at the Department of Microbiology, Tumor and Cell biology and Director of Clinical Genomics at SciLifeLab. “By acting together, contributing resources and skills, we will now get a great opportunity to sort out the hope from the hype in this exciting research field”.

Anders Hamsten, president of Karolinska Institutet said: “This is yet another example of a strong collaborative research effort that Karolinska Institutet has set up with the pharmaceutical industry. The exploration of the human microbiome promises to provide new insights into its role in human physiology and pathology.”

“There is no question that the information coming from this field will lead to innovation in life sciences through improvements in diagnosis, prevention and therapy”, said Per Falk, MD, PhD, Executive Vice President and Chief Scientific Officer at Ferring. “This collaboration with Karolinska Institutet involving SciLifeLab will help to understand the role of the microflora in our key therapy areas and develop innovative treatments to better serve the needs of our patients.”

Inflammatory changes in the brain twenty years before Alzheimer onset

Roughly twenty years before the first symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease appear, inflammatory changes in the brain can be seen, according to a new study from Karolinska Institutet published in the medical scientific journal Brain. The findings of the researchers, who monitored several pathological changes in the brain, suggest that activation of astrocytes at an early stage can greatly influence the development of the disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is characterised by the atrophy of brain neurons, especially those involved in memory, and is our most common dementia disease. Exactly what causes the cells to die is not known, but many years before the first symptoms present themselves, pathological changes occur, such as the deposition of the protein amyloid in the form of amyloid plaques, the accumulation of tau proteins and inflammatory changes that eventually degrade the points of contact between neurons. Exactly when the changes take place along this chain of events remains, however, an unanswered question.

By studying families of people with known Alzheimer’s mutations and who therefore run a much higher risk of developing the disease, the researchers were able to examine changes that appear at a very early stage of the disease. The study included members of families with four different known Alzheimer’s mutations and a group of patients with non-inherited, ‘sporadic’ Alzheimer’s disease. All participants underwent memory tests and scans using PET (positron emission tomography), whereby radioactive tracer molecules with a short half-life are introduced into the brain via injection into the blood.

For this study, the team used the tracer molecules PIB, Deprenyl and FDG to study the amount of amyloid plaques, inflammatory changes in the form of astrocyte activation, astrocytes being the most common type of glial (supporting) cell in the brain. They also studied neuronal function in the brain by measuring glucose metabolism (FDG). In order to monitor the changes over time, the PET scans were repeated after three years for half of the just over fifty participants.

Amyloid plaque and inflammatory changes

The mutation carriers were found to have amyloid plaque and inflammatory changes almost twenty years before the estimated debut of memory problems. The number of astrocytes reached a peak when the amyloid plaque started to accumulate in the brain, and neuronal function, as gauged by glucose metabolism, began to decline roughly seven years before the expected disease symptoms. The individuals from families with inherited Alzheimer’s who did not carry any mutation showed no abnormal changes in their brain.

“Inflammatory changes in the form of higher levels of brain astrocytes are thought to be a very early indicator of disease onset,” explains principal investigator Professor Agneta Nordberg at the Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Center for Alzheimer Research at Karolinska Institutet. “Astrocyte activation peaks roughly twenty years before the expected symptoms and then goes into decline, in contrast to the accumulation of amyloid plaques, which increases constantly over time until clinical symptoms show. The accumulation of amyloid plaque and the increase in number of astrocytes therefore display opposing patterns along the timeline.”

These studies demonstrate that the pathological processes that lead ultimately to Alzheimer’s disease commence many years before symptoms start to show, and that it should be possible to provide early prophylactic or disease modifying treatment. According to the researchers behind the study, the findings indicate that astrocytes can be a possible target for new drugs.

First author of the study is Elena Rodriguez-Vieitez, PhD, senior scientist at Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society. The study was financed by grants from, among others, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (SFF), the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Stockholm County Council/KI ALF fund, Swedish Brain Power, the Swedish Brain Fund, and a GE Healthcare unrestricted research grant.

Our press release about this research

Publication

Diverging longitudinal changes in astrocytosis and amyloid PET in autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease

Elena Rodriguez-Vieitez, Laure Saint-Aubert, Stephen F. Carter, Ove Almkvist, Karim Farid, Michael Schöll, Konstantinos Chiotis, Steinunn Thordardottir, Caroline Graff, Anders Wall, Bengt Långström and Agneta Nordberg

Brain, online 27 January 2016, doi: http://dx.doi:awv404

3D images reveal the body’s guardian against urinary infection

Researchers at Karolinska Institutet have obtained the first 3D structure of uromodulin, the building block of the unique safety net that constantly protects our urinary tract against bacterial infections. Uromodulin also plays a part in certain chronic diseases of the kidney. By analysing the structure of uromodulin, the researchers write in the journal PNAS that they can better understand the mutations that cause these kidney diseases.

Every year, some 150 million people develop an infection of the urinary tract, which makes it one of the world’s most common non-infectious bacterial conditions. Women are most vulnerable, with one in every two developing a urinary infection at some time in life. It is not at all as common in men, but for those who do develop an infection, it can prove very serious.

Since our urinary tracts, unlike other passageways such as the nose, have no protective mucus to help keep bacteria away, the body has developed another strategy to protect itself from attack. Every day, our kidneys produce uromodulin, a sugar-rich protein, which on encountering salt ions in the urinary tract self-assembles into a water-soluble net.

This net contains a large quantity of a particular type of sugar that mimics those found on urinary tract walls. Therefore, the uromodulin net serves as bait for the bacteria that try to attack the body via the urinary tract, trapping and neutralising them before they are excreted from the body into the urine.

Now a team at Karolinska Institutet has managed for the first time to analyse the 3D structure of uromodulin in detail.

“We produced uromodulin using mammalian cells, both as a net that we could examine under a microscope and in a form that can be crystallised,” says principal investigator Luca Jovine, professor of structural biology at the Department of Biosciences and Nutrition at Karolinska Institutet.

Protein crystallography

To obtain a 3D model of uromodulin, the researchers used a technique called protein crystallography, which produces atomic-resolution information on protein molecules by bombarding their crystals with X-rays.

“This enabled us to show for the first time what uromodulin, the most abundant protein in human urine, looks like in detail,” says Professor Jovine.

The information thus produced is also important for understanding certain chronic kidney diseases.

“Now that we know the 3D structure of the protein, we are a step closer to understanding mutations that are responsible for uromodulin-associated kidney diseases,” he adds.

Luca Jovine is also affiliated to the Center for Innovative Medicine, located at Karolinska Institutet's south Stockholm campus in Huddinge. The study was financed with grants from the Swedish Research Council, the Göran Gustafsson Foundation, the Sven and Ebba-Christina Hagberg Foundation, the EMBO Young Investigator Programme and the European Research Council (under the EU’s Seventh Framework Programme). The study was conducted in collaboration with Luca Rampoldi at the San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan, and Daniele de Sanctis at ESRF synchrotron in Grenoble.

Publication

A structured interdomain linker directs self-polymerization of human uromodulin

Marcel Bokhove, Kaoru Nishimura, Martina Brunati, Ling Han, Daniele de Sanctis, Luca Rampoldi and Luca Jovine

PNAS, online the week of 25-29 January 2016, doi:10.1073/pnas.1519803113

Gene often lost in childhood cancer crucial in cells' life or death decision

A gene that is often lost in childhood cancer plays an important role in the decision between life and death of certain cells, according to a new study published in the journal Developmental Cell. Researchers at Karolinska Institutet and Ludwig Cancer Research in Sweden have discovered the process by which that gene, KIF1B-β, kills cells and thereby suppresses tumour development.

Neuroblastoma is the third most common type of tumour in children. Its aggressive nature and the frequency of metastatic disease at diagnosis contribute to the fact that neuroblastoma accounts for almost 15 per cent of childhood cancer fatalities. For the past two decades a region on chromosome 1 that is often missing in neuroblastoma cells has been thought to harbour an important tumour suppressor gene.

"Our data strongly suggest that KIF1Bβ, which is localised on chromosome 1p36, might be such a neuroblastoma tumour suppressor gene", says principal investigator Susanne Schlisio at the Department of Microbiology, Tumor and Cell Biology at Karolinska Institutet and Assistant Member at the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research in Stockholm, Sweden.

Neuroblastoma tumours originate from the same transient progenitor cells—neural crest cells—that give rise to the nervous system along with other tissues. Members of some families are at higher risk than others to develop tumours that originate from these cells due to mutations in specific genes. The research team behind the new study previously discovered that genes mutated in some of the tumours play a central role in determining whether neural crest cells live or die. Neural crest cells that should ordinarily have succumbed to programmed cell death escape that fate when KIF1B-β is lost. Later in life, the cells might develop into cancer cells.

Calcineurin enzyme

In the current study in Developmental Cell, the investigators describe the mechanisms by which KIF1B-β causes cell death. They found that KIF1B-β affects the cells´ power stations, the mitochondria, by activating an enzyme named calcineurin enzyme. Schlisio and her colleagues also show that a critical signal required to induce cell death by fragmenting the mitochondria is compromised by the loss of KIF1B-β. By examining neuroblastoma tumors biopsied from neuroblastoma patients, the researchers demonstrate that loss of KIF1B-β is associated with poor prognosis and reduced survival.

The team also demonstrates a general mechanism that can explain how calcium-dependent signalling by calcineurin is executed. This is a significant finding because the loss of control of calcineurin signalling seems to play a role in many diseases, including neurodegenerative disease, cardiac disease and cancers.

"We conclude that KIF1B-β plays a key role in the decision between life and death for neural crest cells and tumours originating from the neural crest", says Susanne Schlisio. "In time, knowledge of the mechanism by which KIF1B-β induce cell death might prove important in attempts to develop new neuroblastoma therapies."

The research was financially supported by grants from the Ludwig Institute, the Swedish Children Cancer Foundation, the Swedish Research Council (VR) and the Swedish Cancer Society.

Text: Karin Söderlund Leifler

Our press release about this study

More about Susanne Schlisio's research

Publication

The 1p36 tumor suppressor KIF 1Bβ is required for Calcineurin activation, controlling mitochondrial fission and apoptosis

Shuijie Li, Stuart M Fell, Olga Surova, Erik Smedler, Zhi Xiong Chen, Ulf Hellman, John Inge Johnsen, Tommy Martinsson, Rajappa Kenchappa, Per Uhlén, Per Kogner and Susanne Schlisio

Developmental Cell, online January 25, 2016, doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2015.12.029

Parental support has positive effect on children’s eating behaviours

Parental support programmes in areas with the greatest needs can have a positive effect on the consumption of unhealthy food and drink and on weight increases in obese children. This according to a randomised study conducted by Karolinska Institutet and the Stockholm County Council published in the International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity.

Even though school-based programmes promoting healthy eating and physical activity and preventing overweight have had a demonstrable effect, more knowledge is needed on how to best involve the children’s parents. The En frisk skolstart (lit: A healthy school start) programme was therefore launched to support parents in their attempts to promote good dietary habits and physical activity in their preschool children. The present study was carried out in the Stockholm region in areas of low socioeconomic status and where the incidence of overweight and obesity is the highest in the county. The researchers compared 16 preschool classes that were participating in the programme with 15 preschool classes that received no intervention.

The researchers found that the intervention programme gave rise to a significant reduction in the consumption of unhealthy food and drink, such as snacks, ice cream, biscuits, sweets, soft drinks, flavoured milk and fruit juice. Children with obesity at the start of the programme also had an observable reduction in BMI.

“The results are promising, and demonstrate that school initiatives and parental support can promote healthy eating behaviours in six-year-olds with the greatest need,” says project leader Gisela Nyberg, PhD, at Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Public Health Sciences and the Stockholm County Council’s Centre for Epidemiology and Community Medicine. “However, the programme needs enhancing if it is to have a stronger and more lasting impact.”

Two motivational interviews

During the six months of the programme, the parents in the intervention group received health information to read and two motivational interviews. In the school, ten classroom activities were performed with the children, who received assignments to complete at home with their parents. Data on height, weight, diet, physical activity were taken for all of the children at the start of the programme, shortly afterwards and five months after its conclusion. At this fifth-month follow-up, the positive effects of the lower consumption of unhealthy food remained amongst the boys. The programme had no effect on physical activity, but the children’s level of activity was high already from the start.

“The project makes an important contribution to the further development of evidence-based programmes for promoting healthy eating and physical activity and preventing overweight and obesity in children,” says Dr Nyberg. “In the long run, this can help to improve public health and reduce health inequality.”

The study was a collaboration between the “Community nutrition and physical activity” research group at Karolinska Institutet and the Stockholm County Council’s Centre for Epidemiology and Community Medicine. It was financed by the Stockholm County Council, the Martin Rind Foundation and the Sven Jerring Foundation.

Text: Karin Söderlund Leifler (in translation from Swedish)

Publication

Effectiveness of a universal parental support programme to promote health behaviours and prevent overweight and obesity in 6-year-old children in disadvantaged areas, the Healthy School Start Study II, a cluster-randomised controlled trial

G Nyberg, Å Norman, E Sundblom, Z Zeebari och LS Elinder

Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, online 21 January 2016, doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0327-4

New knowledge on why patients with type 2 diabetes present smelling problems

In a study in type 2 diabetic rats, researchers at the Karolinska Institutet have identified alterations in specific nerve cells that are important for odor identification. The findings might explain why type 2 diabetic patients often experience smelling problems and potentially open up a new research field to develop preventive therapies against neurodegenerative diseases in type 2 diabetic patients.

It is well known that patients with type 2 diabetes often suffer from neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease. An early symptom of these neurodegenerative diseases is decreased odor identification ability. This kind of olfactory problem is also often present in patients with type 2 diabetes, suggesting that decreased smelling could be connected with the development of neurodegenerative diseases. However, so far, the nerve cells responsible for these smelling problems in type 2 diabetes have been unclear.

In the current study, published in the journal Oncotarget, researchers at the Karolinska Institutet identified alterations in a group of nerve cells called interneurons, in the piriform cortex of type 2 diabetic rats. The piriform cortex is a brain area that plays an essential role in odor identification and coding. The researchers also showed that the identified neuronal alterations could be counteracted pharmacologically by clinically used anti-diabetic drugs that mimic the mechanism of a hormone that enhances the production of insulin: the glucagon-like peptide 1.

Preventive pharmacological therapies

“Neurodegenerative diseases are highly present within the type 2 diabetic population”, says Grazyna Lietzau, one of the researchers behind the study. “We believe that these findings could be important for the potential development of preventive pharmacological therapies against for example Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s in these patients.”

This study is a result of a collaborative effort of researchers at Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Clinical Science and Education, Södersjukhuset (Cesare Patrone's research group and Thomas Nyström), the Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institutet (Claes-Göran Östenson), and the Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, Medical University of Gdansk in Poland. The work was conceived and directed by Associate Professor Cesare Patrone and Dr Vladimer Darsalia, while Dr Grazyna Lietzau provided important scientific input and directed the experiments. Funders of the study were: the Swedish Heart-Lung foundation, Åhlén-stiftelsen, Stiftelsen för Gamla Tjänarinnor, Tornspiran Stiftelse and Konung Gustaf V:s & Drottning Victorias Frimurarestiftelse.

Publication

Type 2 diabetes-induced neuronal pathology in the piriform cortex of the rat is reversed by the GLP-1 receptor agonist Exendin-4

Grazyna Lietzau, Thomas Nyström, Claes-Göran Östenson, Vladimer Darsalia, Cesare Patrone

Oncotarget, online 5 January 2016, doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6823

Study suggests stem cells may repair dying retinal cells

Researchers at St. Erik Eye Hospital and Karolinska Institutet have for the first time successfully transplanted human retinal pigment epithelial cells derived from stem cells into eyes that are similar to human eyes. The researchers have developed a unique method of creating mature cells differentiated from embryonic stem cells. When transplanted into the retina of human-like animals, the cells protected against experimental macular degeneration. The study is published in Stem Cell Reports.

The most common cause of central visual acuity and reading vision loss among older people in the Western world is the widespread age-related disease macular degeneration. The eye disease results when the supporting cells behind the retina, the "retinal pigment epithelium" cells, slowly die, causing the retinal cells that support vision – the rods and cones – to die as well. The disease has two forms: a wet and a dry form. The wet form can now be halted with drugs, but 90 per cent of patients have the dry form, which currently has no effective treatment.

”Our results suggest that stem cell treatment may help patients with the dry, and so far untreatable, form of macular degeneration,” says Anders Kvanta, Senior Consultant at St. Erik Eye Hospital and Adjunct Professor at Karolinska Institutet, which performed the study together with stem cell researchers Outi Hovatta and Fredrik Lanner.

Read more about the research in an article in Medical Science

Publikation

Xeno-Free and Defined Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells Functionally Integrate in a Large-Eyed Preclinical Model.

Plaza Reyes A, Petrus-Reurer S, Antonsson L, Stenfelt S, Bartuma H, Panula S, et al

Stem Cell Reports 2016 Jan;6(1):9-17

Attention neuron type identified

Researchers at Karolinska Institutet have identified for the first time a cell type in the brain of mice that is integral to attention. By manipulating the activity of this cell type, the scientists were able to enhance attention in mice. The results, which are published in the journal Cell, add to the understanding of how the brain’s frontal lobes work and control behaviour.

The frontal cortex of the brain plays a crucial part in cognitive functions, including everyday mental processes such as attention, memory, learning, decision-making and problem-solving. However, little is known about how the frontal cortex performs these mental processes, including which neuronal cell types are involved. A longstanding theory holds that parvalbumin-expressing neurons (PV cells) play a key role in cognition; now, however, researchers show that PV cells seem to be not only essential to attention; it also appears that it is enough to optimise PV cell activity in order to enhance attention.

The team focused on attention since it is a cognitive process that is affected in many neuropsychiatric disorders. The scientists trained mice to perform a task requiring a high degree of attention, and recorded the activity of hundreds of individual neurons in the frontal cortex while the animals repetitively performed the task.

“We found that the activity of the PV cells reflected the animals’ level of attention,” says lead investigator Marie Carlén at the Department of Neuroscience. “The PV cells were highly active if the animals were attentive, and less active when they were inattentive. The differences were so great that we were able to predict if an animal would perform the task successfully or not merely by looking at the activity of the PV cells.”

Used optogenetics

The researchers used optogenetics to influence PV-cell activity during the seconds the animals needed to be attentive. They found that the animals’ attention was impaired when they either inhibited or changed the pattern of this activity. However, they also found a type of manipulation that could improve attention. During certain cognitive processes a category of brain waves known as gamma oscillations (30-80 Hz) increases in prefrontal cortex, and when the scientists activated the PV cells at gamma frequencies the animals solved the task more times.

While cognitive problems are common in mental disorders such as schizophrenia, ADHD and autism, there is currently no effective medicine available.

“Our findings tie together a number of previous observations on PV cells and their involvement in cognition and neuropsychiatric disorders, and demonstrate this cell type’s critical role in cognition and psychiatry,” says Dr Carlén. “The findings also show that it’s possible to enhance cognitive functions by altering the activity of a single neuron type, which is quite astonishing when you think of how complex the brain is. PV cells are therefore a very interesting target for the pharmaceutical industry.”

The study was conducted at Karolinska Institutet and financed with grants from the European Research Council (ERC), the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Ragnar Söderberg Foundation, and the Swedish Brain Foundation (Hjärnfonden).

View our press release about this study

Publication

Prefrontal Parvalbumin Neurons in Control of Attention

Hoseok Kim, Sofie Ährlund-Richter, Xinming Wang, Karl Deisseroth, Marie Carlén

Cell, online 14 January 2016, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.038

Mosquito net safe to use in inguinal hernia repair

Sterilised mosquito nets can replace costly surgical meshes in the repair of inguinal (groin) hernias without further risk to the patients. This makes mosquito nets a good alternative for close to 200 million people in low-income countries suffering from untreated groin hernias. These are the results of a Swedish-Ugandan study presented in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

An inguinal hernia is a defect or a hole in the abdominal wall around the groin, through which fat, intestines and sometimes other abdominal organs can be pressed into a sack-like protrusion. It is a common complaint in both high and low-income countries, and the only effective treatment is surgery. Without surgery, inguinal hernias can cause considerable suffering and life-threatening complications that cause some 40,000 fatalities a year.

Hernia surgery is also one of the world’s most common surgical procedures, accounting for around 20 million operations every year. However, almost 200 million sufferers do not receive surgery, most of who live in the poorer parts of the world; the operations that are performed use techniques that are clearly inferior to those used in high-income countries. One of the reasons that too few people in low-income countries are given the chance of effective treatment is that the scientifically tested meshes available on the market are very expensive.

“Commercial hernia meshes cost 100 dollars or more, which is too much for the health services and people living in poor countries,” says Dr Jenny Löfgren, researcher at Umeå University’s Department of Surgical and Perioperative Sciences. “So instead, doctors and surgeons in several countries have been using mosquito nets, but whether they are effective and safe hasn’t been given sufficient study until now.”

Working with colleagues from, amongst other institutions, Karolinska Institutet and Uganda’s Makerere University, Dr Löfgren has therefore conducted a large randomised clinical trial to compare mosquito net with the regular commercial mesh used in hernia operations. The study, which is published in NEJM, involved over 300 adult males from rural eastern Uganda who were randomly assigned to receive the one or the other type of reinforcement. The operations were performed by four experienced surgeons at the Kamuli Mission Hospital, and the participants were subsequently monitored for a year as regards patient satisfaction, post-operative complications or recurrence.

No significant differences

The results show that the post-operative complications that occurred were normally mild and that there was no significant differences between the groups. This was also true of self-rated satisfaction. Only one patient in the mosquito-net group had a recurrence. All in all, the study shows, according to the team, that sterilised mosquito net is fine for use in hernia surgery without compromising patient safety and treatment efficacy.

“These results are of great potential benefit to the many millions of people who lack access to good surgical care for their hernias,” says study project leader and surgeon Dr Andreas Wladis, associate professor at Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Clinical Science and Education at Stockholm South General (Söder) Hospital. “The next step will be to motivate greater resource allocation to treat hernia patients and plan for how mosquito nets could be used for hernia surgery on a larger scale.”

The study is part of Dr Jenny Löfgren’s doctoral thesis, which she recently defended at Umeå University. It was funded by grants from several bodies, including the Swedish Society of Medicine, the Swedish Research Council, Swedish Rotary, the Church of Sweden and the Capio Research Foundation. Swedish hospitals and companies also contributed either donated or discounted equipment.

View our press release about this study

Publication

A randomized trial of low cost mesh in groin hernia repair

Jenny Löfgren, Pär Nordin, Charles Ibingira, Alphonsus Matovu, Edward Galiwango, Andreas Wladis

NEJM 14 January 2016, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505126

New role for motor neurons discovered

A new study presented in the journal Nature could change the view of the role of motor neurons. Motor neurons, which extend from the spinal cord to muscles and other organs, have always been considered passive recipients of signals from interneuronal circuits. Now, however, researchers from Karolinska Institutet have demonstrated a new, direct signalling pathway through which motor neurons influence the locomotor circuits that generate rhythmic movements.

Locomotion is essential to all animals and is based on a carefully balanced interaction between the muscles and the brain. Nerve cells are typically able to both receive and generate electrical impulses, which are then relayed to other nerve cells. The nerve cells that make contact with the muscles are called motor neurons, and for almost a century they have been regarded as passive receivers of the detailed motor programmes generated and elaborated by networks of nerve cells in the spinal cord. According to this model, motor neurons relay the signals faithfully and unidirectionally to the muscles.

“We have now uncovered an unforeseen role of motor neurons in the elaboration of the final program for motor behaviour,” says principal investigator Abdel El Manira at Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Neuroscience. “Our unexpected findings demonstrate that motor neurons control locomotor circuit function retrogradely via gap junctions, so that motor neurons will directly influence transmitter release and the recruitment of upstream excitatory interneurons.”

Easy to manipulate genetically

The study was conducted using zebrafish, a common animal model in neurobiological research because they are transparent and relatively easy to manipulate genetically. Through a combination of different methods, the team has shown that there is a direct link via electrical synapses or gap junctions, between motor neurons and the excitatory interneurons that generate rhythmic swimming motions in the fish.

These synapses directly connect two neurons, and enable the transfer of electrical signals between these neurons. With the aid of optogenetics, the researchers selectively silenced the activity of motor neurons and showed that they have a strong influence on the locomotor circuit function via gap junctions.

“This study represents a paradigm shift that will lead to a major revision of the long held view of the role of motor neurons,” says Professor El Manira. “Motor neurons can no longer be considered as merely passive recipients of motor commands – they are an integral component of the circuits generating motor behaviour.”

The study was performed by Jianren Song, Konstantinos Ampatzis and Rebecka Björnfors together with Abdel El Manira and financed with grants from the Swedish Research Council, Karolinska Institutet and the Swedish Brain Fund.

Our press release about this study

More on Abdel El Manira's research

Publication

Motoneurons control locomotor circuit function retrogradely via gap junctions

Jianren Song, Konstantinos Ampatzis, E. Rebecka Björnfors and Abdeljabbar El Manira

Nature, online 13 January 2016, doi: 10.1038/nature16497

Comment on media report in Vanity Fair

An article in the magazine Vanity Fair on January 5 claims that a researcher and former visiting professor at Karolinska Institutet provided false information in his resume. For this reason, Karolinska Institutet has started an investigation to verify the accuracy of the information the researcher submitted to KI prior to his employment in 2010.

In this investigation, KI will contact the universities where the researcher was previously employed. The investigation will be conducted expeditiously, but for the moment, it is not possible to say when it will be completed.

Children of murdered women run higher risk of mental disorder

Research from Karolinska Institutet shows that the offspring of women murdered by their partners run an elevated risk of mental disorder, substance abuse and criminal behaviour.

In the study, which is published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, the researchers studied children of the victims of intimate partner femicide (IPF). The study included 261 perpetrators and 494 children. The researchers found that mental disorder and a history of violent crime were more common amongst the perpetrators than the rest of the population, and that subsequent mental disorder, substance abuse, criminal behaviour and self-harm were common amongst the children.

For most women who are murdered in Sweden, the perpetrator is a current or former male partner, and children who are thus deprived of their mother can develop mental health problems. In the present study, the researchers used national registries to identify all men who had killed a woman with whom they had offspring between 1973 and 2009, and to collect data on prior psychiatric morbidity, attempted suicide and violent criminal behaviour. The perpetrators were compared with controls randomly selected from the general population. The children were followed longitudinally over several years and also matched with population controls.

The team behind the study concludes that the risk factors for IPF include mental disorders and prior violent criminal behaviour, and that offspring older than 18 years at the time of their mother’s murder run an elevated risk of committing violent crime and of premature death, including suicide. Self-harming and violent criminal behaviour were also more common amongst these children.

“Children who lose their mother before the age of 18 have a worse prognosis than other children, in terms of mental disorder, including substance abuse,” says Henrik Landström Lysell, doctoral student at Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Clinical Neuroscience. “The healthcare and social services should give priority to these children’s psychosocial needs, regardless of age.”

The study was financed by the National Crime Compensation Authority of Sweden and the Swedish Prison and Probation Service.

Publication: “Killing the Mother of One’s Child: Psychiatric Risk Factors Among Male Perpetrators and Offspring”, Henrik Lysell, MD; Marie Dahlin, MD, PhD; Niklas Långström, MD, PhD; Paul Lichtenstein, PhD; and Bo Runeson, MD, PhD. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 5 January 2016.