KI News

Attempted suicide among young people can be reduced by 50 percent

A new study published in journal The Lancet outlines a programme for preventing suicidality among young people. The results provide strong endorsement for a method whereby school students learn to discover signs of mental ill-health in themselves and their friends, while they are also trained to understand, interpret and manage challenging emotions. The European study was led from Karolinska Institutet, and researchers now hope to see the method reach a large number of young people in European schools.

At a global level, suicide is the second leading cause of death in the age group 15-29. Only road traffic accidents cause more fatalities in this age group. At the same time, there has been a lack of knowledge about which strategy is best for preventing suicidal behaviours in young people. A major EU-funded study which embraces more than 11,000 school students from 168 schools in ten EU countries has therefore evaluated different strategies for prevention of suicidality in young people.

Three methods

In the study, schools were randomized to receive one of three suicide prevention models or alternatively become part of a control group. The three methods were:

An US method whereby teachers and other school personnel are trained to recognise signs of suicidality and motivate the students to seek help.

A classroom screening test where psychiatrists, psychologists and counsellors identify students with mental health problems and refer them to treatment.

The Awareness Programme which was developed by researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden and Columbia University in the USA. It is a method whereby students learn both to recognise signs of mental health problems and cultivate good mental health with short lectures, posters in classroom environments and a more comprehensive brochure to take home. Students were also invited to take part in supervised role-play where they could explore their emotions and learn coping strategies for a variety of difficult life situations that could lead to suicidal behaviours. The educational programme lasted five hours over four weeks.

No measures were taken in the control group except for putting up the posters that were part of the Awareness Programme in the classrooms.

The study provides results showing the effectiveness of the Awareness Programme – which gives students a tool to exercise influence over their mental health – in preventing attempted suicide and serious suicidal thoughts with plans how to commit suicide. One year after completing the programme, the number of attempted suicides and serious suicidal thoughts and planned suicides in this group was 50% lower compared with the control group.

Professional health care personnel

In the two other groups, where the responsibility for the students’ mental health rested exclusively with the teacher or professional health care personnel, the proportion was the same as in the control group.

“This study provides much-needed evidence for the effectiveness of universal school-based public health programmes designed for students. The study shows that it possible to implement suicide prevention programmes in schools with good results. Now we can take the step from following statistics that indicate the seriousness of the problem, towards actively and comprehensively using the Awareness Programme in schools. We also plan to develop the method into a modern web-based solution such as a mobile phone app to reach as many young people as possible,” said Danuta Wasserman, Professor at the Department of Learning, Informatics, Management and Ethics, and head of the National Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention of Mental Ill-Health (NASP) at Karolinska Institutet, Sweden.

The study was funded by an EU grant from the Seventh Framework Programme (FP7). It is led from NASP, which also is WHO’s collaborative partner in the field.

View a press release about this research

Publication

A Randomised Controlled Trial of School-based Suicide Preventive Programmes; The Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe Study (SEYLE)

Danuta Wasserman, Christina W Hoven, Camilla Wasserman, Melanie Wall, Ruth Eisenberg, Gergö Hadlaczky, Ian Kelleher, Marco Sarchiapone, Alan Apter, Judit Balazs, Julio Bobes, Romuald Brunner, Paul Corcoran, Doina Cosman, Francis Guillemin, Christian Haring, Miriam Iosue, Michael Kaess, Jean-Pierre Kahn, Helen Keeley, George Musa, Bogdan Nemes, Vita Postuvan, Pilar Saiz, Stella Reiter-Theil, Airi Varnik, Peeter Varnik & Vladimir Carli

The Lancet, online 9 January 2015

Urban Lendahl new Secretary for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

Professor Urban Lendahl has been elected as the new Secretary of the Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet and Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine. Lendahl succeeds Professor Göran Hansson, who has been has been elected Permanent Secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Lendahl will take office starting January 1, 2015.

Professor Lendahl is Professor of Genetics at the Department of Cell- and Molecular Biology, Karolinska Institutet. He was a member of the Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine 2007-2013 and Chairman of the Nobel Committee 2012. He has been a member of the Nobel Assembly since July 1, 2000.The present Secretary, Professor Göran Hansson, has been elected Permanent Secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and will take up this position on July 1, 2015. Professor Hansson remains a member of the Nobel Assembly.

- Urban Lendahl has high integrity and is extremely well respected amongst his colleagues. I am delighted to have this opportunity to work together with Professor Lendahl as he takes on this important task. It has been a pleasure to work together with Professor Hansson and I look forward to further interactions in his role as Permanent Secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and Member of the Nobel Assembly, says Professor Juleen R. Zierath, Chairman of the Nobel Committee at Karolinska Institutet.

Endogenous retroviruses important in immune response

A new study in Science, in which researchers from Karolinska Institutet participated, shows that retroviruses may not only be harmful to humans. According the findings, so called endogenous retroviruses, which are included in the genome of each person, could play an important role in the body’s immune defense against common bacterial and viral pathogens.

Retroviruses are best known for causing contagious scourges, such as AIDS or cancer. They are able to insert into the genomic DNA of cells that they infect, including germ cells. Millions of years ago, retroviruses were included in the human genome through a process called retrotransposition. About 45 percent of a person’s DNA is of retroviral origin, and some of the better preserved copies are termed endogenous retroviruses (ERV). These genetic elements do not cause infection, and it has been unclear if they have any function at all.

Writing in the journal Science, researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center and Karolinska Institutet have found that when B cells are activated by large polymeric antigens such as polysaccharides of bacteria, they rapidly produce protective antibodies in what is termed the type II T-independent antibody response. This response, central to the body’s defense against common bacterial and viral pathogens, is dependent on ERV.

“We believe that, once retroviruses have become part of the host germline, they are subject to selection for beneficial effects just like any other part of the genome, and their ability to activate an innate immune response seems to have been utilized to the benefit of the host,” says Dr. Gunilla Karlsson Hedestam, Professor at the Department of Microbiology, Tumor and Cell Biology at Karolinska Institutet.

Reverse transcriptase

The research team shows that within activated B cells the ERV are driven to express RNA copies of themselves, which in turn are copied into DNA by an enzyme called reverse transcriptase. The RNA copies of endogenous retroviruses are detected by a protein called RIG-I, and the DNA copies are detected by another protein called cGAS. These two proteins send further signals that enable the B cells to sustain their activated state, proliferate, and produce antibodies.

“Mice lacking elements of the RIG-I or cGAS pathways show diminished responses to type II T-independent antigens, and mice lacking both pathways show almost no antibody response at all to these antigens. Moreover, reverse transcriptase inhibiting drugs also partially inhibit the type II T-independent antibody response”, observes Gunilla Karlsson Hedestam.

Principal investigator of this current study has been Dr. Bruce Beutler, Professor and Director of UT Southwestern Center for the Genetics of Host Defense, who shared the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. The work was funded by donations from the Lyda Hill Foundation and the Kent and JoAnn Foster Family Foundation, and by NIH grants.

View a commentary in Science about the findings

View a press release from UT Southwestern Medical Center

Publication

MAVS, cGAS, and endogenous retroviruses in T-independent B cell responses

Ming Zeng, Zeping Hu, Xiaolei Shi, Xiaohong Li, Xiaoming Zhan, Xiao-Dong Li, JianhuiWang, Jin Huk Choi, Kwan-wenWang, Tiana Purrington, Miao Tang, Maggy Fina, Ralph J. De Berardinis, Eva Marie Y. Moresco, Gabriel Pedersen, Gerald M. McInerney, Gunilla B. Karlsson Hedestam, Zhijian J. Chen, Bruce Beutler

Science online 18 December 2014, doi: 10.1126/science.1257780

Physical activity improves survival for men with localized prostate cancer

A new study from Karolinska Institutet shows that men with localized prostate cancer who engaged in higher levels of physical activity had lower rates of overall mortality and lower rates of prostate cancer-specific mortality, compared with less active counterparts. The findings are being published in the journal Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

Researchers analyzed data from 4,623 men in the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden Follow-up Study, who were diagnosed with localized prostate cancer from 1997 to 2002 and followed until 2012. Data on physical activity was obtained through paper- and web-based questionnaires about lifestyle. Information about cause and date of death were obtained from the Swedish Cause-of-Death Registry.

The results show that men with localized prostate cancer who walked or cycled for 20 or more minutes a day had a 30 percent decreased risk of death from any cause (overall mortality) and a 39 percent decreased risk of death as a result of their disease (prostate cancer-specific mortality) compared with those who walked or cycled less. For those who engaged in 1 or more hours of exercise per week, overall and prostate cancer-specific mortality rates were decreased by 26 percent and 32 percent, respectively, compared with less active counterparts.

“Our results extend the known benefits of physical activity to include prostate cancer-specific survival,” says Stephanie Bonn, MSc, a doctoral student at the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics. “However, it is important to remember that our results are based on group level. An individual’s survival depends on many factors, but physical activity is one factor that individuals can modify. Hopefully, our study can motivate men to be physically active even after a prostate cancer diagnosis.”

The study was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society, and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working life and Welfare, and it was headed by Katarina Bälter, PhD, Senior lecturer at the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics.

Publication

Physical activity and survival among men diagnosed with prostate cancer

Stephanie E Bonn, Arvid Sjölander, Ylva Trolle Lagerros, Fredrik Wiklund, Pär Stattin, Erik Holmberg, Henrik Grönberg, Katarina Bälter

Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, online 19 December 2014

Website statistics can predict emergency room visit volumes

A new study from Karolinska Institutet and Södersjukhuset suggests that statistics on website visits may be used to predict the level of demand at emergency departments. The study, which is being published in the journal Annals of Emergency Medicine, shows a significant correlation between Internet searches on a regional medical website and next-day visits to regional emergency departments.

Using Google Analytics, researchers tallied and graphed Internet searches of the Stockholm Health Care Guide (SHCG), a regional medical website, over a one-year period and compared them to emergency department visits over the same period. Visits to the SHCG between the hours of 6:00 p.m. and midnight were significantly correlated to the number of emergency room visits the next day.

The most accurate forecasting for emergency department visits was achieved for the entire county, with an error rate of 4.8 percent. The error rate of forecasting individual hospitals’ emergency department visit rates based on Internet searches ranged from 5.2 percent to 13.1 percent. (An error rate below 10 percent was considered good performance, as this is on par with other methods already described for forecasting emergency room visit volumes.)

The research team behind the finding, conclude that website analytics may be used to predict emergency room visits for a geographic region, as well as for individual hospitals. Looking forward, researchers also suggest that it might be possible to create a model to predict emergency department visits that would enable better matching of personnel scheduling to emergency room volumes.

All co-authors are affiliated to Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Clinical Science and Education, Södersjukhuset (Stockholm South General Hospital). Annals of Emergency Medicine is the peer-reviewed scientific journal for the American College of Emergency Physicians.

View a press release from the American College of Emergency Physicians

Publikation

Forecasting Emergency Department Visits Using Internet Data

Andreas Ekström, Lisa Kurland, Nasim Farrokhnia, Maaret Castrén & Martin Nordberg

Annals of Emergency Medicine, published online as corrected proof on December 4th, 2014, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.10.008

Swede of the Year Johan von Schreeb started the Ebola training course

The Ebola outbreak will get out of hand in early December if attempts to combat the disease do not intensify, predicted the UN in mid-October. Since then, the government has ring-fenced half a billion kronor to stop the spread of the disease, and Karolinska Institutet has trained some 100 individuals to work in the affected areas. The course was instigated by Johan von Schreeb, surgeon and docent at KI’s Centre for Disaster Medicine and recipient of Focus magazine’s Swede of the Year title.

The course was created as a direct result of the acute lack of healthcare workers in West Africa. It is two days long and involves several experts. Earlier this autumn, Johan von Schreeb returned home from Sierra Leone, where he was working for the World Health Organisation. To him, like other experts in the area, it is clear that the Ebola crisis can not be solved by money alone.

“We can’t rely on organisations like Doctors without Borders to handle the situation on their own and must send Swedish medical personnel down,” says Dr von Schreeb.

“Ebola training for fieldworkers” was put together in just over a week, which probably makes it the most hastily organised course in KI’s history. As late as just a few days before the scheduled start on 13 October, a training centre was being set up in accordance with specifications issued by Doctors without Borders for how an Ebola treatment centre (ETC) is to be organised for the care of patients with a suspected or confirmed infection.

The physical location of the training camp is the old gymnastics hall on the KI campus. The course focuses on handling the influx of patients into the camp and on training important things like handling samples and putting on and taking off protective clothing, including rubber boots, double gloves, breathing mask and visor.

Another important aspect is prioritising the patients. It is essential to preventing the spread of Ebola that only infected people are brought into the ETC.

Nurse Anneli Eriksson, who is leading the course with Dr von Schreeb, has a great deal of experience working and training personnel in the field. Earlier this autumn she returned home from one of Doctors without Borders’s largest camps in Liberia.

“The safety of medical staff is top priority, but we need to prepare ourselves if we’re to work in a way that doesn’t expose us to danger,” says Ms Eriksson.

Even though her camp was the organisation’s largest, the staff still had to turn away some of the sick. The principle there is effectively “one corpse out, one patient in”. The training also includes the handling of dead bodies and safe burials.

Originally, the idea was for KI to hold three courses and then evaluate them. But at the start of November, an additional course was quickly arranged to meet the need for more trained medics in Liberia. Despite the short notice, the course was over-subscribed and the majority of its participants are already booked to travel. Drumming up interest in the course is thus no problem. If the shoe pinches anywhere, it is with the employers.

“If Swedish medical staff are to go to Africa and help, they must be released by their managers in the healthcare services, which isn’t always the case,” says Dr von Schreeb.

The training is organised by the Centre for Excellence for Disaster Medicine at KI in association with the National Board of Health and Welfare, Doctors without Borders, the Public Health Agency of Sweden, and the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB).

Text: Jenny Ryltenius

How Ebola spreads: Ebola is caused by a virus and is a type of viral hemorrhagic fever. It is passed on through direct contact with infected bodily fluids, such as vomit, saliva, blood, coughs and sneezes, and with infected dead bodies. Infection is most likely to occur during the care and handling of the sick, so those at greatest risk are family members and medical personnel. Source: The Public Health Agency of Sweden and Doctors without Borders.

"I'm deeply honoured", says Johan von Schreeb in the Focus magazine. Read the full article (in Swedish only).

Hexagonal patterns in Aula Medica foyer celebrate Nobel lectures

The 2014 Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine, John O'Keefe, May-Britt Moser and Edvard Moser, provided a mix of data old and new as well as a good few laughs at the Nobel lectures in the Karolinska Institutet auditorium on Sunday 7 December.

By eleven when Aula Medica opened, some people had already been waiting outside for an hour so as not to miss the Nobel lectures, which began two hours later. If it had not been for the red candles and a Christmas tree in the entrance, one might have forgotten it was December, given the bright sunshine and above-zero temperatures.

After more queuing indoors, where posters of the Nobel-winning discovery of the brain’s own GPS system were quickly snapped up, the members of the audience were finally able to find their places in the auditorium itself.

On welcoming everyone to the lectures, Karolinska Institutet’s vice-chancellor, Professor Anders Hamsten, handed over to Professor Hans Forssberg to introduce the three laureates.

First up was Professor John O’Keefe, who quoted a poem that he and a colleague wrote back in 1978: “Space plays a role in all our behaviour. We live in it, move through it, explore it, defend it”.

His research was about the cells that make up a positioning system in the brain: the hippocampal place cells that he himself discovered, plus other cells like the grid cells in the entorhinal cortex, that the Mosers discovered.

His lecture included data suggesting that part of the positioning system appears in neonate rats even before they have had any real sensory input from their surroundings. He also described a water maze for laboratory animals invented by a colleague to test one of his early hypotheses.

“This water maze is still the most popular and most potent test of hippocampal function available today,” he said.

Professor Edvard Moser was next, and lectured on the hexagonal patterns that the grid cells create in the brain, adding that they are also present in other, different contexts, such as the windows of Aula Medica.

“I suspect that the Nobel Committee has been planning this day for a long time,” he said, raising a chuckle from the audience, some of whom perhaps noted afterwards that it wasn’t only the exterior of the auditorium that had a hexagonal pattern, but also the floor of the foyer and the paving outside.

Professor May-Britt Moser began her lecture with a short film that also raised a peal of laughter from the audience. It was of a mouse trying to carry a biscuit up onto a platform, which she compared to a scientist trying to solve scientific problem. After many failed attempts, the mouse finally succeeded.

“Science is a field where the impossible can become possible,” she said.

She then went on to talk about how the grid cells and other cells influence the place cells, about cells in the entorhinal cortex that detect speed, and about how smells can be associated with locations.

Edvard Moser and May-Britt Moser both spent some time at John O’Keefe’s lab at the start of their careers.

“It was the most efficient learning period of my life,” said Edvard Moser during his lecture.

It is the kind of interaction that the Mosers and John O’Keefe are still engaged in to this day. During the post-lecture reception May-Britt Moser mentioned that next year John O’Keefe will be at Norway’s Teknisk‐Naturvitenskapelige Universitet in Trondheim, where the Mosers work, as a visiting professor.

And Edvard Moser said that the three of them have together invited 160 guests to a joint party in the Nobel Forum later that evening.

“This is a research field in which everyone knows each other really well, and we wanted to invite all those people who have done their bit for science,” he said. “But of course we couldn’t invite everyone to the Nobel party.”

Text: Lisa Reimegård

Photo: Erik Cronberg

Watch the lectures on YouTube:

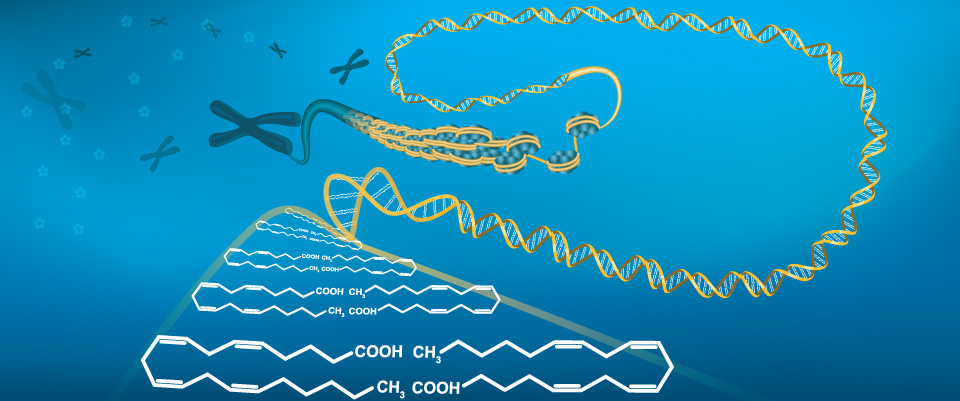

Long-term endurance training impacts muscle epigenetics

A new study from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden shows that long-term endurance training in a stable way alters the epigenetic pattern in the human skeletal muscle. The research team behind the study, which is being published in the journal Epigenetics, also found strong links between these altered epigenetic patterns and the activity in genes controlling improved metabolism and inflammation. The results may have future implications for prevention and treatment of heart disease, diabetes and obesity.

“It is well-established that being inactive is perilous, and that regular physical activity improves health, quality of life and life expectancy”, says Professor Carl Johan Sundberg, Principal Investigator at the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology. “However, exactly how the positive effects of training are induced in the body has been unclear. This study indicates that epigenetics is an important part in skeletal muscle adaptation to endurance training.”

Epigenetics can simply be described as temporary biochemical changes in the genome, caused by various forms of environmental impact. One type of epigenetic change is methylation, where a methyl group is added to or removed from a base in the DNA molecule without affecting the original DNA sequence. If genes are considered the hardware of cells, then epigenetics can be seen as their software.

One-legged cycling

The current study included 23 young and healthy men and women who performed supervised one-legged cycling, where the untrained leg served as a control. The volunteers participated in 45 minutes training sessions four times per week during a three month period. Performance was measured in both legs before and after training. In the skeletal muscle biopsies, markers for skeletal muscle metabolism, methylation status of 480 000 sites in the genome, and activity of over 20 000 genes were measured.

Results show that there were strong associations between epigenetic methylation and the change in activity of 4000 genes in total. Genes associated to genomic regions in which methylation levels increased, were involved in skeletal muscle adaptation and carbohydrate metabolism, while a decreasing degree of methylation occurred in regions associated to inflammation.

Important novel finding

An interesting and potentially very important novel finding was that a majority of the epigenetic changes occurred in regulatory regions of our genome, so called enhancers. These sequences in our DNA are often situated far away from the actual genes they regulate, in comparison to so called promoter regions, which traditionally have been considered to control most of the gene activity.

“We found that endurance training in a coordinated fashion affects thousands of DNA methylation sites and genes associated to improvement in muscle function and health”, says Carl Johan Sundberg. “This could be of great importance for the understanding and treatment of many common diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, but also for how to maintain a good muscle function throughout life. Interestingly, we also saw that there were epigenetic differences between male and female skeletal muscle, which may be of importance to develop gender specific therapies in the future.”

First study-authors are Maléne Lindholm and Francesco Marabita, both at Karolinska Institutet. The study has been funded by grants from the Swedish National Centre for Research in Sports, Torsten Söderberg Foundation, the STATegra network within the EU’s FP7, Stockholm County Council, and the Swedish Research Council.

View a press release about this research

Publication

An integrative analysis reveals coordinated reprogramming of the epigenome and the transcriptome in human skeletal muscle after training

Maléne E Lindholm, Francesco Marabita, David Gomez-Cabrero, Helene Rundqvist, Tomas J Ekström, Jesper Tegnér & Carl Johan Sundberg

Epigenetics, first online 7th December 2014, doi:10.4161/15592294.2014.982445

The election is over – at least for KI

The academic election year at Karolinska Institutet, during which deans, assistant deans and faculty representatives were voted onto the University Board and the three internal boards, drew to a close on 3 December.

The deans and assistant deans were elected back in the spring, and on 3 December the identities were established of the faculty members who will be sitting on the boards that the deans will be heading. This means that the boards of Higher Education, Doctoral Education and Research are now ready to set to work for their new term of office that will last from 1 January to 31 December 2017.

Earlier in the autumn it was also announced who will be representing the teachers on Karolinska Institutet’s highest executive body, the University Board, from the new year. Elias Arnér will be continuing for another three years, joined by new members Anna Karlsson and Lena Von Koch. All three were elected by KI’s teachers with voting rights in September by means of electronic ballot.

The faculty representatives on the internal boards were elected in turn by a nomination assembly comprising 67 departmental representatives.

The election of the deans last spring was decided after a consultative election by teachers with voting rights at Karolinska Institutet, whereupon the final decision was taken by Vice-Chancellor Anders Hamsten.

Nine young researchers awarded Wallenberg Academy Fellows at Karolinska Institutet

The Knut and Alice Wallenbergs Foundation has selected nine researchers from Karolinska Institutet as Wallenberg Academy Fellows 2014. They are to receive funding between SEK 5 and 9 million over five years. Four of the researchers are international recruitments to Karolinska Institutet.

Jenny Mjösberg

People with a history of inflammatory bowel disease, such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, have a higher risk of developing colon cancer. As a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, Jenny Mjösberg will study the role played by a newly discovered family of cells that belong to the immune system, innate lymphoid cells, in the development of tumors. Jenny Mjösberg will share her time between the Department of Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Huddinge and Linköping University.

Read more here

Jenny Mjösberg group

Björn Högberg

Associate Professor Björn Högberg from the Department of Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, can control the folding of DNA molecules by programming the genetic code: this is called DNA origami. As a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, he will use DNA origami as a tool for investigating the interactions between cells and mapping the differences in gene expression between healthy cells and cancer cells.

Read more here

Högberg lab

Pekka Katajisto

People, who can keep their stem cells young, can keep their bodies young. As a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, Pekka Katajisto seeks methods that will help stem cells to retain their vitality. In doing so, he will try to delay aging. Dr Pekka Katajisto is at the Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, and Academy Research Fellow, Academy of Finland. He will continue his research at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm.

Read more here

Katajisto lab

Yenan Bryceson

When genetic defects sideline cells of the immune system, serious and often deadly diseases may result. Dr Yenan Bryceson at the Department of Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, and Adjunct Professor at the Department of Internal Medicine, University of Bergen, will use the latest methods in gene technology to map the mutations that disrupt the functioning of two white blood cells: cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells. The knowledge generated by the project will be used by Yenan Bryceson to develop sensitive diagnostic methods for diseases that are linked to these lymphocytes. The hope is that this also results in better treatment methods.

Read more here

Yenan Bryceson Group

Edmund Loh

Each year, around 100 people in Sweden suffer serious meningitis caused by a meningococcus bacterium that is normally found in the nose and throat. For some reason, the bacteria penetrate the mucous membrane and enter the brain. As a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, Edmund Loh will conduct research into why these bacteria suddenly become dangerous. Edmund Loh is currently Swedish Research Council Postdoctoral Fellow at The Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford. As a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, Edmund Loh will be based at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm.

Read more here

Andreas Olsson

Researchers know much about how personal experiences of distressing events give rise to fear, but we also learn fear from others and we learn to be afraid of others. What governs these types of social learning? Andreas Olsson, Associate Professor at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, will look for the answer to these questions during his time as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow.

Read more here

Andreas Olsson Group

Robert Månsson

Sometimes the genetic mutations that cause diseases are located outside the actual genes, in parts of the DNA that regulate the gene’s activity. Dr Robert Månsson at the Center for Hematology and Regenerative Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, will pair genes that influence blood cells with the correct control region in the DNA. The aim is that this will lead to a better understanding of blood cancer.

Read more here

Robert Månsson Group

Peder Olofsson

Many common diseases are linked to an overactive immune system and inflammation in the body. Dr Peder Olofsson, from the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, USA, will investigate a new and revolutionary discovery: that nerve cells regulate the immune system. The aim is to reduce inflammation by modulating the signals that are sent between the nerves and the immune system. As a Wallenberg Academy Fellow Peder Olofsson will setup this research at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm.

Read more here

Eduardo Villablanca

In inflammatory bowel diseases, such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, chronic inflammation occurs in the gut when uncontrolled immune responses are misdirected against self, microbiota-derived and/or environmental antigens. Eduardo Villablanca will find out why: what happens when the dialog between the gut flora, intestinal cells and cells from the immune system is lost. Eduardo Villablanca is Instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Assistant Immunologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and researcher at Broad Institute, Cambridge, USA. He will move his activities to Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm.

Read more here

Villablanca Lab

About Wallenberg Academy Fellows

Sweden’s largest private investment in young researchers, Wallenberg Academy Fellows, has announcement 29 new Wallenberg Academy Fellows 2014. The programme is financed by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and supports some of Sweden’s, and the world’s, most promising researchers in medicine, natural sciences, engineering sciences, humanities and social science.

All the Wallenberg Academy Fellows participate in a mentoring programme that aims to strengthen their academic leadership and to provide them with the knowledge and experience necessary to improve the commercialisation of their research results. The programme’s international element also contributes to the increased internationalisation of the Swedish research environment, thus fulfilling several of the criteria that are in demand to increase the competitiveness of Swedish research.

KI students highly commended for undergraduate paper

Two students from Karolinska Institutet, Mimmi Mononen and Maria Movin, were highly commended by The Undergraduate Awards at the summit meeting in November.

The international award body The Undergraduate Awards (UA) recognises and rewards undergraduate students across 25 disciplines, ranging from business and engineering to visual arts and midwifery. Mimmi Mononen was highly commended for her paper on the role of fractalkine in microglia-glioma communication, and Maria Movin for her work on the impact of childhood asthma and atopy on growth in early adolescence.

The 120 winners and highly commended entrants, representing 50 universities, were selected from 4,792 submissions. The awards were presented at the 2014 UA Global Summit in Dublin, Ireland, on 21st November. Linnea Jonsson Axelsson and Elin Persson from Karolinska Institutet were also highly commended, but could not attend the summit.

Miia Kivipelto and Jonas Fuxe awarded ”Best PI at KI”

Miia Kivipelto, professor at Ageing Research Center (ARC) and the Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society (NVS), and Jonas Fuxe, senior researcher at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics (MBB) at Karolinska Institutet, have both received the honorable title ”Best PI at KI” 2014 by the KI Postdoc Association.

The annual award was introduced this year and postdocs have nominated and voted for the best nominated PIs (Principal Investigators). Among eleven nominees, Miia Kivipelto and Jonas Fuxe received the most and an equal number of votes. In the nominations, it was mentioned that Miia Kivipelto ”has created a cooperative and stimulating work environment, in which her team is motivated, productive and successful”, while Jonas Fuxe was described as ”a great leader who has restored the postdoc's passion for science”. Both were awarded the prize on 14 November at the “Mentoring for success in science” workshop, which was co-organised by Junior Faculty and the journal Nature Genetics.

Increased infant mortality rates among children of overweight women

Children face a greater risk of dying during the first year of life if the mother is overweight. This is the conclusion drawn by a new study from Karolinska Institutet published in the scientific periodical BMJ.

In Sweden, around 3 in 1,000 children die during their first year. In a global context, this is one of the lowest infant mortality rates, but there are still ways to reduce infant mortality further, even in Sweden. One risk factor that should be preventable is overweight and obesity among young women.

"Our research shows that risk in children increase as their mothers become increasingly overweight”, says Stefan Johansson, senior consultant at the Sachs' Children's Hospital in Stockholm, and researcher at Karolinska Institutet. “For an individual woman, regardless of her weight, the risk of her child dying is very small. However, our results are still important from a population perspective, as overweight is common among women of a childbearing age.”

Over 1 million women

The study is based on data from the Swedish Medical Birth Register and encompasses over 1 million women and their 1.8 million children born in the period 1992–2010. When analysing this extensive set of data, the researchers investigated whether the mothers' body mass index (BMI) in early pregnancy was associated with the risk of the infant death. Of all the women, 24 per cent were overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9) and 9 per cent were obese (BMI 30.0 and up).

An increasing BMI was associated with an increasing rate of infant mortality; from 2.4 cases per 1,000 women of normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9) to 5.8 cases per 1,000 women with the most pronounced obesity (BMI 40.0 and above). Relatively speaking, the increase in risk was moderate for children of overweight women (BMI 25.0–29.9) or mild obesity (BMI 30.0–34.9), at 25 and 37 per cent respectively. In women with more pronounced obesity (BMI 35.0 and up), the child's relative risk was doubled.

In two previous projects, the research group have found that increasing BMI in women increases the risk of premature births and hypoxia during birth; two complications that can lead to the child's death.

"However, when we looked at the causes of infant deaths, we realised that there were several different underlying problems,” says Stefan Johansson. “Other than premature birth and hypoxia, congenital abnormalities and diseases during the neonatal period also contributed to the higher mortality rate.”

Promote public health

The researchers hope their results do not worry women with a high BMI, as it is still rare for infants to die in Sweden. The most important message of this study, according to Stefan Johansson, is the importance of broad-based strategies to promote public health. A healthier society with a population being more normal weight would also be beneficial to the health of newborns.

"Another important message relates to antenatal and neonatal care. Deliveries involving overweight women, and especially those with a significantly elevated BMI, should be considered to carry a higher risk”, says Stefan Johansson. “The health service has a responsibility to be particularly observant in these cases, to minimise risks to both mother and child.”

Financial support for the study was provided by an unrestricted grant from Karolinska Institutet (Distinguished Professor Award to Professor Sven Cnattingius), and from the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare.

View a press release about this research

Publication

Maternal overweight and obesity in early pregnancy and risk of infant mortality – a population-based cohort study in Sweden

Stefan Johansson, Eduardo Villamor, Maria Altman, Anna-Karin Edstedt Bonamy, Fredrik Granath, Sven Cnattingius

British Medical Journal (BMJ) 2014;349:g6572, online 2 December 2014

Causal link between antibiotics and childhood asthma dismissed

In a new register study in the scientific journal BMJ, researchers at Karolinska Institutet are able to dismiss previous claims that there is a link between the increased use of antibiotics in society and a coinciding rise in childhood asthma. The study includes half a million children and shows that exposure to antibiotics during pregnancy or early in life does not appear to increase the risk of asthma.

Several previous studies have shown that if the mother is given antibiotics during pregnancy or if a small child is given antibiotics in early life, the child has an increased risk of developing asthma. These studies have led to a widespread belief of a causal link. However, according to the researchers at Karolinska Institutet, there is reason to question the results of these studies.

It may be difficult to diagnose asthma in small children since newly presented symptoms of asthma can be misinterpreted as a respiratory infection. The children may then have received antibiotics for the supposed infection – which actually is asthma – and the antibiotic treatment is then suspected to have caused the asthma that is later discovered. Another explanation is that respiratory infections themselves increase the risk of asthma, regardless of whether or not they are treated with antibiotics. A third explanation is that previous studies have not given sufficient consideration to other factors shared within families that may increase the risk of asthma, such as genetics, home environment and lifestyle.

Exposed to antibiotics

"Thanks to the Swedish population based registers we have been able to conduct a study designed to include factors that were previously not included. Our results show that there does not appear to be a causal link between early exposure to antibiotics and asthma, which is also valuable from an international perspective," says Anne Örtqvist, physician and doctoral student at the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at Karolinska Institutet.

The study includes almost 500,000 children born in Sweden between January 2006 and December 2010. As a first step, the researchers studied the children that had been exposed to antibiotics in fetal life, when their mothers were treated during pregnancy, and found that the risk for asthma in the child was increased by 28%. The researchers then included other risk factors such as genetics, home environment or lifestyle by performing comparative analyses within families with several children, and found that the relationship between antibiotics during pregnancy and asthma disappeared.

In brief, there were a large number of children in the study where one sibling had asthma and where another had been exposed to antibiotics early in life without developing asthma. The number of such families was large enough to rule out a causal link between antibiotics during pregnancy and asthma in the child, according to the study.

Conducted sibling analyses

In the next step, children who had received antibiotics early in life were studied. The researchers compared if the risk of developing asthma after treatment with antibiotics was equally high if the child had been treated for a skin-, urinary tract- or respiratory infection. They found that this was not the case. The risk was instead much higher after being treated for a respiratory infection, which indicates that the link was due to newly presented asthma being misinterpreted as a respiratory infection and treated with antibiotics, or that the respiratory infection in itself increases the risk of asthma, regardless of whether or not it is treated with antibiotics.

When the researchers conducted sibling analyses divided by skin-, urinary tract- and respiratory infection, the link between antibiotics treatment and asthma disappeared.

"Our results indicate that there is no causal link between antibiotics treatment and childhood asthma. But it is still important to use antibiotics very carefully, considering the threat of antibiotic resistance. We also want to emphasise the importance of correctly diagnosing children with airway symptoms, where suspected symptoms of asthma should be separated from respiratory infection," says Catarina Almqvist Malmros, Pediatrician and Professor at the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, who led the study.

The study is financed by project grants from the Swedish Research Council and SIMSAM, grants provided by the Stockholm County Council (ALF project), the Strategic Research Programme in Epidemiology at Karolinska Institutet and the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation.

View a press release about this research

Publication

Antibiotics in fetal and early life and subsequent childhood asthma: nationwide population based study with sibling analysis

Anne K Örtqvist, Cecilia Lundholm, Helle Kieler, Jonas F Ludvigsson, Tove Fall, Weimin Ye, and Catarina Almqvist

British Medical Journal, online 28 November 2014, BMJ 2014;349:g6979

Another of this year’s Nobel prizes linked to KI

This year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry also has strong links to life sciences and to KI. Super-resolution has revolutionised light microscopy and given scientists new tools for studying events at a molecular level in living cells.

The limit of light microscopy was calculated back in the 1800s: approximately 0.2 micrometers. Resolution any higher than this was considered a physical impossibility. However, in the past decade this limit has been elegantly circumvented with lasers and fluorescent markers, enabling biologists to study processes in living cells at a much higher resolution than ever before. It is an innovation that has earned Stefan Hell, Eric Betzig and W.E. Moerner the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Sweden’s centre for super-resolution microscopy is Advanced Light Microscopy (ALM) at SciLifeLab in Solna. ALM is a national research infrastructure resource that is open to scientists from around the country.

“Super-resolution gives us unprecedented access to molecular mechanisms,” says ALM director Hjalmar Brismar, whose research group at the Department of Women’s and Children’s Health uses the technique. “We don’t only see the presence of a protein, but also where it is and how it moves.”

The earliest adopters of the new tool have been neuroscientists and microbiologists.

Text: Anders Nilsson

View a news clip from SVT on the Nobel-winning discovery. (In Swedish.)

Secretagogin triggers stress process in the brain

Researchers at Karolinska Institutet and MedUni Vienna in Austria have identified a new molecular mechanism to regulate stress. In a study published in the EMBO Journal, they show that the protein secretagogin plays an important role as a trigger in the release of the stress hormone CRH, which only then enables stress processes in the brain to be transmitted to the pituitary gland and onwards to the body.

"If, however, the presence of secretagogin, a calcium-binding protein, is suppressed, then the Corticotropin Releasing Hormone, CRH, might not be released in the hypothalamus of the brain thus preventing the triggering of hormonal responses to stress in the body," says Tibor Harkany, a Professor of Neurobiology at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, Karolinska Institutet, and affiliated to the MedUni Vienna.

The hypothalamus requires the assistance of CRH to stimulate the production and release of the hormone ACTH from cells in the pituitary gland into the blood stream. Thus, ACTH reaches the adrenal cortex and once there stimulates the production and release of further hormones, including the vital stress hormone cortisol. Upon stress, the hypothalamus responds by releasing CRH and thus produces the critical signal orchestrating also ACTH and cortisol secretion. However, if this cycle is interrupted, it is not possible for acute, and even chronic, stress to arise.

Extended understanding

Secretagogin was discovered 15 years ago by researchers at the MedUni Vienna, in connection with research on the pancreas. The researchers behind the current study now hope that their findings will provide an extended understanding of how hormonal responses to stress are generated.

"This could result in a further development, where secretagogin is deployed as a tool to treat stress, perhaps in people suffering from mental illness such as depression, burn out or posttraumatic stress disorder, but also in cases of chronic stress brought on by pain”, says Tomas Hökfelt, MD, Senior Professor at the Department of Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet.

The study has been funded by the Swedish Research Council, The Swedish Brain Foundation, Petrus and Augusta Hedlund’s Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, Karolinska Institutet, MedUni Vienna, the French National Research Agency, the European Commission, and the Wellcome Trust.

Learn more in a press release from MedUni Vienna

Publication

A secretagogin locus of the mammalian hypothalamus controls stress hormone release

Roman A Romanov, Alán Alpár, Ming-Dong Zhang, Amit Zeisel, André Calas, Marc Landry, Matthew Fuszard, Sally L Shirran, Robert Schnell, Árpád Dobolyi, Márk Oláh, Lauren Spence, Jan Mulder, Henrik Martens, Miklós Palkovits, Mathias Uhlén, Harald H Sitte, Catherine H Botting, Ludwig Wagner, Sten Linnarsson, Tomas Hökfelt & Tibor Harkany

EMBO Journal, online first 27th November 2014, doi: 10.15252/embj.201488977

Professor Bob Harris – with an award and a sword

Getting the perfect hit on an opponent with a bamboo sword has much in common with medical research – at least if you ask Professor Bob Harris, who has been a competitor and instructor in the Japanese martial art of kendo for many years. One of this year’s two recipients of the KI pedagogy prize, he is the first to receive it for his contributions to doctoral education.

“When doing kendo, you have to study your opponent during combat and look for weaknesses. It’s the same with research. It’s all about probing your way ahead and constantly striving to do things better.”

His willingness to develop has also driven his passion for doctoral education. On being one of the two winners of this year’s pedagogy prize at KI along with teacher and researcher Lars Henningsohn at Clintec, he was acclaimed for having “been a driving force behind bringing an educational perspective into doctoral education.”

“I’m happiest for the sake of doctoral education, and that the prize shows that the educational side of things is important there,” he says.

His box of pedagogical tricks and activities contains webinars, lectures and seminars that students can stream from the net. He was also an early user of audience response systems, which enable his students to answer a question by pressing buttons and give immediate feedback on the compiled results. Robert Harris, or Bob as everyone calls him, is an advocate of interactivity in teaching and hopes to make that kind of technology more accessible, as he feels it is woefully underused at present. However, it is, he says, his commitment to changing views on doctoral education that won him the prize.

“I’m fairly headstrong and not afraid of conflict,” he says. “I see myself as innovative, in terms of both research and doctoral education, and have high expectations, as I want to see wholesale improvements.”

Bob Harris feels that there has been far too much emphasis on the results of the students’ research, and that the Swedish word for doctoral education, forskarutbildning (literally “researcher education”), is itself a problem.

“Is it research or is it education? Many people think that research is what you do in the lab and education is what you do when you go away on a course. We want to move away from the idea that they’re two separate things.”

When a doctoral student defends his or her thesis, it is up to the examination board to judge if he or she has attained the relevant intended learning outcomes. In recent years, the Board of Doctoral Education, on which Bob Harris sits, has been trying to raise awareness of these objectives amongst the students and their supervisors. By checking a student’s progress along the way, a supervisor, and the student, will both be able to judge if the objectives have been achieved and if a doctor’s hat is within reach.

“Now, seven years on, we can see that the intended learning outcomes are an increasingly common feature of a defence,” says Bob Harris. “Doctoral education is about the training as well, not just the results presented in the published articles.”

Doctoral education is a special kind of education, since it revolves so much around the collaboration of student and supervisor. The environments in which students work can be very different, and this depends in large part on their supervisors. And as for what makes a good supervisor, Bob Harris’s answer is simple:

“They have time, that’s the main thing. The time and interest to see someone grow. And in return you get back some solid research.”

He has attended many supervisor courses over the years, and admits that it can be something of a challenge for teachers who hold the same course year in year out to remain inspired when the same topics crop up again and again.

“The secret is to see every group as a fresh opportunity. Each group is different and you have to be flexible enough to be able to adapt to them. So even if the subject’s the same, the way you teach it is different every time, and that’s what makes it enjoyable.”

Back to kendo. Whether he’s teaching kendo or supervising doctoral students, there’s one thing that matters to Bob Harris, and that’s that each individual develops according to his or her abilities.

“If all I can do is teach the stuff I know myself, I’d be a pretty rubbish teacher. I want them to be better researchers and better supervisors than I am. I’m happy to get whacked by my kendo students. I’m a tough trainer and a tough director of studies, because I expect a great deal from my students. But I’m a nice person too.”

Text: Karin Söderlund Leifler

Photo: Gustav Mårtensson

Two studies identify pre-cancerous state in the blood

Researchers from Karolinska Institutet together with American colleagues have uncovered an easily detectable, “pre-malignant” state in the blood that significantly increases the likelihood to develop blood cancer. The discovery, which was made independently by two research teams, opens new avenues for research aimed at early detection and prevention of blood cancer. The findings are being published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Most research on blood cancer to date has focused on studying the genomes of advanced cancers, to identify the genes that are mutated in various cancer types. These two new studies instead looked at somatic mutations – mutations that cells acquire over time as they replicate and regenerate within the body – in DNA samples collected from the blood of individuals not known to have cancer or blood disorders.

Taking two very different approaches, the teams found that a surprising percentage of those sampled had acquired a subset – some but not all – of the somatic mutations that are present in blood cancers. These individuals were more than ten times more likely to go on to develop blood cancer in subsequent years than those in whom such mutations were not detected. The pre-malignant state identified by the studies becomes more common with age, and appears with in more than 10% of those over the age of 70. Carriers of the mutations are at an overall 5% risk of developing some form of blood cancer within five years.

Limited clinical use

Pre-malignant stage can be detected simply by sequencing DNA from blood. However, researchers point out that the findings at the moment are of limited clinical use at the moment, since there are no working therapies for cancer mutations in healthy people.

The two studies were headed from Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and Harvard Medical School in Boston, USA. The work with collecting and analyzing data at Karolinska Institutet was led by Christina Hultman, a Professor at the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, in collaboration with Dr. Anna Kähler, Dr. Johan Lindberg, and Professor Henrik Grönberg. Funding bodies has been the Stanley Foundation, the National Institute of Health, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Society, StratCan and Strat Neuro at Karolinska Institutet, among others.

Learn more in a press release from Broad Institute

Publications

‘Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes’, Jaiswal, S et al., New England Journal of Medicine, Online First November 26, 2014. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617

‘Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence’, Genovese, G et al., New England Journal of Medicine, Online First November 26, 2014, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409405.

2014 Nobel prize winners: “It was a wonderful moment“

Fantastic! A shock! One of the best things that’s ever happened to me! When John O’Keefe, May-Britt Moser and Edvard Moser are asked how it felt to win this year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, they all gush with joy and surprise.

“It’s the most prestigious award a scientist can receive,” says John O’Keefe, professor of cognitive neuroscience at University College London, UK, who discovered the positioning cells that earned him the 2014 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

By registering neuronal activity in the brains of free-roaming rats, he found that certain cells of the hippocampus were activated when the rat was in a particular location.

“It was a wonderful moment when I saw the correlation,” he says. “A vast amount of literature, written over thousands of years, has tried to come to grips with the problem of understanding the connection between the space we experience and the physical world.”

John O’Keefe was one of the first scientists to register the activity of individual nerve cells in free-roaming animals, and says that new techniques that reveal new things are behind many important scientific breakthroughs, and that he would like to see more such research in the future.

“We must get better at giving researchers, particularly junior ones, the freedom to explore using new techniques and new ideas, and sometimes to make mistakes without feeling the pressure of having to publish articles in respected journals,” he says.

He adds that breakthroughs can also only occur when the scientist understands that he or she has discovered something important. His fellow laureates, May-Britt and Edvard Moser, both professors of neuroscience at Norway’s Teknisk‐Naturvitenskapelige Universitet in Trondheim, agree:

Focusing is crucial

“John O’Keefe and we made our discoveries in similar ways: we saw something that we hadn’t been expecting, and continued to study it, and in both cases it was a combination of luck and a readiness to handle the unexpected,” says Professor Edvard Moser, adding that courage, patience, creativity and the ability to focus on the right questions are also crucial to scientific success.

He and May-Britt Moser discovered the so-called grid cells in the entorhinal cortex, a part of the brain close to the hippocampus, after observing that these cells not only were activated when a rat passed by a certain point in its environment but also that they gave off a signal when it was at nearby locations.

“At first we suspected a regular pattern, but when the rats were allowed to roam over a larger area, a hexagonal grid emerged,” says Professor May-Britt Moser. “A special neuron was activated when a rat passed one of the points of a hexagon. What’s fascinating is that nothing in the rat’s environment had this shape. The pattern is one of a very few known to be created by the brain itself.”

The grid cells, the place cells and other cells that indicate head orientation, speed of movement and nearby obstacles are part of a system that probably exists in all mammals and that functions as an internal GPS. The system also plays an important part in how we create memories.

John O’Keefe first met May-Britt and Edvard Moser when they were doctoral students at Oslo University in Norway.

“I could tell right away that these two would become stars in the world of science, and was happy when they then asked to come to my lab to learn our techniques,” he says. “They turned out to be two of fastest learners I’ve ever supervised. Today, we’re not just colleagues interested in the same part of the brain, but very good friends too.”

O'Keefe a mentor

May-Britt and Edvard Moser describe John O’Keefe as a mentor, who taught them, amongst many other things, about the importance of maintaining a high level of quality in their research to ensure that it is reliable and replicable.

“Excellent research must be excellent every step of the way, and this takes efficient research teams and healthy, happy laboratory animals,” says May-Britt Moser.

When asked how their research will benefit humankind, all three laureates mention Alzheimer’s disease.

“The disease onsets with lesions in the part of the brain where these cells are fond, and some of the first symptoms are an impaired positional sense and an impaired memory,” says Edvard Moser. “Since the disease develops very slowly, it might be possible to stop it if we can find out what’s going wrong. But first, we have to understand how the normal brain works.”

He and May-Britt Moser are now focusing on finding out how all cell types in the advanced positional system interact, and on trying to understand how the grid pattern arises.

“The brain is complex but conservative, and often uses the same trick again and again,” says Edvard Moser. “Maybe we can learn something about completely different cognitive functions as well.”

They are also, he continues, both interested in understanding how the positional system integrates with motor cells.

Lot to learn from KI

“I should think there’s a lot here to learn from Karolinska Institutet, where a lot of research is going on about how the brain controls movement and takes us from A to B.”

John O’Keefe plans to continue his work on the hippocampus, but has also started to take an interest in the amygdala, part of the brain that belongs to the limbic system.

“I’m driven in my research by curiosity, and go to the lab every day in the hope of finding something new and, ideally, important,” he says. “As I mentioned before, new technologies can pave the way for new discoveries, and right now we’re planning to develop methods for registering electric signals from thousands of nerve cells at once.”

All three agree that the Nobel Prize is a hallmark of quality. While May-Britt Moser hopes that the prize will also boost the recruitment of top researchers to her and her husband’s groups, John O’Keefe is more sceptical about the effect.

“Maybe it’ll be easier to get research grants, but then again it could also be harder,” he says with a laugh.

Text: Lisa Reimegård

John O’Keefe was born in 1939 in New York City, USA, and is both a US and British citizen. After earning his PhD in physiological psychology in 1967 at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, he moved to England to research at University College London, where he was appointed professor of cognitive neuroscience in 1987. John O’Keefe is currently head of the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre for Neural Circuits and Behaviour at the same university.

May‐Britt and Edvard Moser were both born in Norway, she in 1963 and he in 1962. They studied psychology at Oslo University and took their PhDs in neurophysiology in 1995, after which they did their postdoc research at the University of Edinburgh and with John O’Keefe at University College London. In 1996 they returned to Norway and established a research laboratory at the Teknisk‐Naturvitenskapelige Universitet in Trondheim. Edvard Moser was made professor of neuroscience in 1998, and May‐Britt Moser in 2000. May-Britt Moser is currently director of the university’s Centre for Neural Computation and Edvard Moser of the Kavli Institute for Systems Neuroscience in Trondheim.

Nobel Lectures in Physiology or Medicine 2014, December 7 at Karolinska Institutet

Students eat pizza with Vice-Chancellor

The mood was free, as were the pizzas. KI students assembled last Monday to ply Vice-Chancellor Anders Hamsten with questions.

“It’s easy for a vice-chancellor to become invisible, so every opportunity to come and talk to the students is good,” said Professor Hamsten.

The students were enticed into the Huddinge campus university library with free pizza, and as they munched their capricciosa and veggie slices, they listened to the Vice-Chancellor answer questions about KI’s new strategy, Strategy 2018.

“I came for the combination of a free lunch and an interesting Q&A session,” said medical student Magdalena Lublin.

The questions concerned contact with business, a smoking ban, a gym, computer support and much more besides.

When it came to IT support, Professor Hamsten didn’t mince his words:

“KI slaps its brow, you could say. This is a huge problem right now. Our own IT platform is sub-standard and security is poor. But we’re aware of this and are working on it. But then the county council’s own network must also work properly, but that’s up to them, not us.”

Medical student Michael Plattén raised the paradox that while it’s KI’s mission to promote health, there’s no smoking ban outdoors or a gym.

“We really should lead by example, and show that we take our own health seriously too,” he said.

There’ll be a gym, but not for another two or three years, promised the Vice-Chancellor, who also said that it would be impossible to ban smoking outdoors.

Biomedicine Master’s student Peter Solsjö, the moderator for the afternoon, wanted to see closer contacts with the business community – ideally some kind of corporate fair – to give KI students a better view of the entire labour market.

“Yes, that’s a good idea,” agreed Professor Hamsten. “In fact, a committee has been set up with the pro-Vice-Chancellor to look at things like how doctors and engineers in Huddinge can come together to learn from each other. Maybe we need some kind of common student union building.”

Afterwards, a dozen or so people remained behind to ask further questions.

The free pizza and Q&A session will be repeated on the Solna campus on 3 December, this time exclusively in English.

Photo: Erik Cronberg